Clayton Kershaw won the NL Cy Young in 2011, and he won it again in 2013. You could argue that he had a good case to get it over R.A. Dickey in 2012 and should be on a run of three in a row, but you can also argue that Roy Halladay and Cliff Lee basically put up identical seasons to what he did in 2011, so we’ll call it even. It was almost impossible to make a case for anyone other than him being the best pitcher in baseball entering the season, and now that Justin Verlander is declining and Jose Fernandez is injured, it’s now not possible at all. He is, simply, the best. It’s why I took him at No. 3 in the recent ESPN Franchise Player draft ahead of Yasiel Puig and Masahiro Tanaka and everyone else who wasn’t Mike Trout or Bryce Harper.

Clayton Kershaw won the NL Cy Young in 2011, and he won it again in 2013. You could argue that he had a good case to get it over R.A. Dickey in 2012 and should be on a run of three in a row, but you can also argue that Roy Halladay and Cliff Lee basically put up identical seasons to what he did in 2011, so we’ll call it even. It was almost impossible to make a case for anyone other than him being the best pitcher in baseball entering the season, and now that Justin Verlander is declining and Jose Fernandez is injured, it’s now not possible at all. He is, simply, the best. It’s why I took him at No. 3 in the recent ESPN Franchise Player draft ahead of Yasiel Puig and Masahiro Tanaka and everyone else who wasn’t Mike Trout or Bryce Harper.

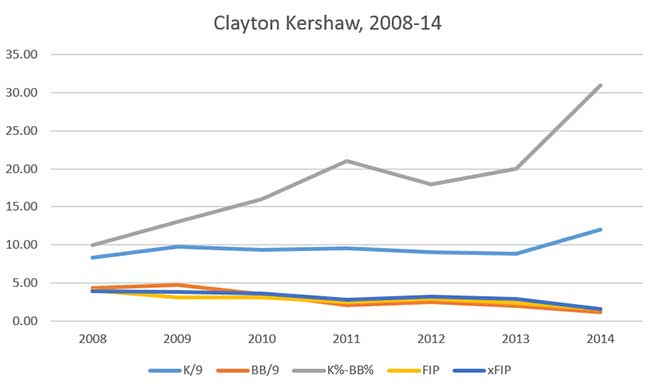

The scary thing is, he was already the best, and now he’s getting better. No, really:

I get that these stats aren’t all on the same scale — FIP isn’t a percentage isn’t a per-nine — but I think it illustrates the point well enough. Kershaw’s strikeouts have increased considerably this year. His walk rate keeps declining. The combination of the two — that’s K%-BB%, in gray — is astronomical. His FIP and xFIP keep declining right along with his walk rate. Not shown here, if only because it would have skewed the scale too much, is his groundball percentage, which has generally been in the 40-46% for his career, and is now 58.1.

He’s striking out more, he’s walking fewer, he’s getting more grounders…. and he was already, even without that, the best. What he’s doing just isn’t fair. And now, finally, we can get to my point: if you look at any list of the best pitchers in baseball, you won’t find him. You’ll see Tanaka and Yu Darvish and Felix Hernandez and Stephen Strasburg and Jon Lester, but you won’t see Kershaw.

It’s easy to understand why, of course, because thanks to the month-plus he spent on the disabled list thanks to a strained lat, he doesn’t have enough innings to qualify. After pitching in Australia on March 22, we didn’t see him again until May 6, so he has 10 starts and 64.1 innings. Most of the other top pitchers have 14 or 15 starts (Hernandez has 16) and something like 90 to 110 innings pitched. In order to be eligible for the ERA title, which is the traditional cutoff for these things, a pitcher must have 162 innings in a season, or one per game. Since last night was the 74th game of the Dodgers season, it’s going to take him a while to catch up. Assuming that he’ll pitch seven innings every five Dodger games, he would pick up enough innings to qualify in four or five more starts, with the two numbers converging around 92, depending on how his starts go.

Over the course of his truncated season, Steamer and ZiPS project him to have about 175 innings pitched, a far cry from his usual total of well over 200. But will that be enough, presuming continued success, to get him another Cy? That’s where it gets a little tough.

Over the course of his truncated season, Steamer and ZiPS project him to have about 175 innings pitched, a far cry from his usual total of well over 200. But will that be enough, presuming continued success, to get him another Cy? That’s where it gets a little tough.

In the history of the award, dating back to 1956, only 10 times has a pitcher with fewer than 200 innings won it, but none of those are great comparables. Seven were relievers, which isn’t really relevant, and two (Fernando Valenzuela in 1981 and David Cone in 1994) did it in strike-shortened seasons. The other was Rick Sutcliffe‘s 1984, which was just weird: after a mediocre start to the season in Cleveland, he was traded to the Cubs on June 13, where he then proceeded to rip off an insane 16-1 stretch in just 150.1 innings, though he had 244.1 total. (He shouldn’t have won it, anyway; Dwight Gooden should have.)

So for Kershaw to capture another Cy, he’s going to have to do something that’s never really been done before, which is win over the hearts and minds of voters in fewer than 200 innings without extenuating circumstances. At a minimum, he’ll need to qualify for the leaderboards, which shouldn’t be a problem. But then he’s going to have to prove that he’s so far ahead of everyone else that it’s undeniable, because great pitching over many innings is more valuable than great pitching over fewer innings.

Working in Kershaw’s favor, I suppose, is that the cream of the pitching crop this year are all in the AL, between Tanaka, Darvish, and Hernandez, and that Fernandez and Matt Harvey are both out of commission. You look at the NL, and the competition is a bit lighter. Strasburg has been phenomenal, even if no one wants to admit it. Adam Wainwright just keeps on ticking, presuming his recent elbow soreness is nothing major. Johnny Cueto, as we saw earlier this month against the Dodgers, has been unbelievable, and if he can somehow keep that ERA starting with a one, he’s going to have a lot to say about this. Kershaw’s going to have to make it undeniably clear that despite fewer innings, he’s the best — and if you lower the innings requirement to include him, he’s certainly doing that right now. I imagine having one of the best-pitched games ever under his belt would be an effective tiebreaker.

To be honest, I don’t really need Kershaw to win awards to know how great he is. We know how flawed the process is — just remember Mike Trout and Matt Kemp losing deserved MVPs just because their teams didn’t win enough games — and losing to Strasburg or Wainwright or any of them would hardly be an insult. But I imagine Kershaw cares, and I know the Dodgers do. As we get closer and closer to “it’s not just a Hall of Fame career, but an inner-circle Hall of Fame career,” piling up awards like these help. He’s already one of just 17 pitchers with two. Only eight have three. This is historic stuff.

Oh, and… he’s still only 26. Still. Only. 26.

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog