The original title of this post was going to be ‘Grant Dayton is Good Enough for the Eighth Inning.’ The whole point of the article was that he has a very good chance to be better than Joe Blanton was last year. However, Paul Swydan already wrote that article (more or less) for MLB.com and the research that I was using to write that article led to a different place: Grant Dayton has one of the best four-seam fastballs in all of baseball. It could be the best, depending on how you look at it.

That’s a bold claim, and the first place to look for confirmation is the radar gun, but there’s not much to see there. Dayton’s four-seamer averages just under 93 MPH, and the fastest he can get is around 95. That velocity is slightly above-average for a left-handed reliever these days, which says a lot about how baseball has evolved in the last ten years. And yet, Dayton can do this:

All three strikeouts? Four-seam fastballs. That fastball is something special. That’s good, because he threw it 77 percent of the time overall, and was at an 85 percent rate by the end of the season.

Among relievers with at least 20 innings pitched in 2016, Dayton had the sixth-highest strikeout rate at 38.6 percent. He was one spot below Aroldis Chapman, and one spot above Craig Kimbrel. 35 of Dayton’s 39 strikeouts ended with that fastball. Only Sean Doolittle and Ryan Buchter ended a higher percentage of their strikeouts with a four-seamer last year.

—–

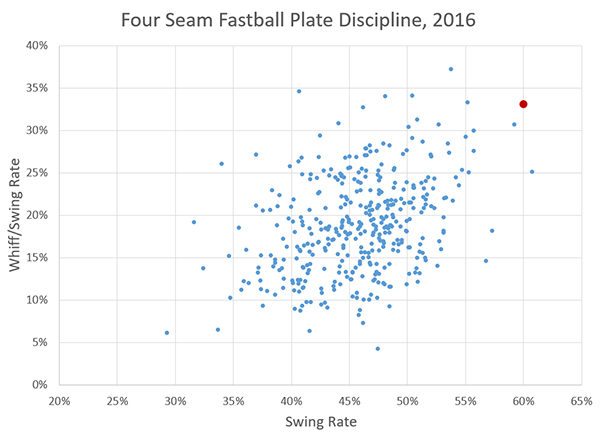

There are so, so many ways to show how special Dayton’s four-seamer was last year, so let’s start here: the components of what makes up swinging strike rate. Every dot on the chart below is a pitcher who threw at least 200 four-seam fastballs last season. On the horizontal axis is how often a batter swung at the fastball. On the vertical axis is how often a batter missed the ball when they did swing. A higher swing rate isn’t always better, but it can be if the batter misses a lot. Grant Dayton is shown in red.

Breaking the chart into individual leaderboards, here were the highest four-seam fastball swing rates last year:

| Pitcher | Swing Rate |

|---|---|

| Rick Porcello | 60.8% |

| Grant Dayton | 60.1% |

| Sean Doolittle | 59.3% |

| Liam Hendriks | 57.4% |

| Blaine Boyer | 56.8% |

And whiff/swing rates:

| Pitcher | Whiff/Swing Rate |

|---|---|

| Nick Vincent | 37.2% |

| Rich Hill | 34.6% |

| Carl Edwards | 34.1% |

| Jeurys Familia | 34.0% |

| Aroldis Chapman | 33.3% |

| Grant Dayton | 33.0% |

The two axes can then be combined into whiffs/pitch (still just four-seam fastballs):

| Pitcher | Whiff/Pitch Rate |

|---|---|

| Nick Vincent | 20.0% |

| Grant Dayton | 19.8% |

| Aroldis Chapman | 18.4% |

| Sean Doolittle | 18.2% |

| Carl Edwards | 17.2% |

The average swinging strike rate on four-seam fastballs last season was 8.7 percent. Dayton’s swinging strike rate was almost 20 percent. That’s better than an average slider. That’s why, as Swydan pointed out in his article, Dayton’s swinging strike rate was 26th of 511 pitchers with at least 20 innings pitched last season. What’s more impressive is that he did it without an above-average secondary pitch.

—–

As shown above, batters are extremely aggressive against Dayton’s fastball. He was very good at getting batters to chase it out of the zone (third-highest four-seam chase rate). Batters were equally aggressive in the strike zone (third-highest in-zone swing rate): over 80 percent of the time Dayton threw the ball into the PITCHf/x strike zone, batters swung, and Dayton hits the zone a lot. Combine the high zone rate and the high swing rate, and even after you subtract all of the whiffs there’s potentially a large number of in-zone fastballs to be put into play, which can be dangerous.

In order to better judge that impact, it’s worth going into a statistically weird area: foul balls. Fouls can be a problem because there hasn’t been a lot of research done on how reliable foul ball rate can be from year to year, but at least we can use it to look back. Subtracting whiffs and fouls from total swings can get total balls put into play, or the only pitches that can result in hits. This ignores walks and contact quality, but we already know that Dayton’s control is excellent and we’ll get to contact quality later. Additionally, we’ll only look at pitches thrown inside the strike zone, since the goal is to see if batters’ aggression works to their advantage despite the whiffs.

Combine these factors and you in-zone ball-in-play swing rate, or the following formula:

![]()

Below is a list of the lowest BIP/ZoneSwing rates for four-seam fastballs last season.

| Pitcher | BIP/ZoneSwing |

|---|---|

| Nick Vincent | 17.7% |

| Ian Krol | 18.0% |

| Grant Dayton | 20.6% |

| Hector Neris | 21.5% |

| Alex Reyes | 22.8% |

If normalized by total pitches instead of total swings, Dayton remains in the top ten.

I’m not going to claim that this stat is predictive or even that it’s good, but it shows is that batters’ high aggression against Dayton’s fastball did not hurt him last year. Normally a pitcher wants to get a batter to swing at balls and look at strikes, and Dayton was only good at the former. However, when betters did swing at strikes, they didn’t do anything with them. That works too. If batters are going to adjust to Dayton’s fastball, getting more aggressive isn’t the answer since they’re hyper-aggressive already. Getting less aggressive probably won’t help either because of Dayton’s excellent control. Instead, they’ll need to do better when they do swing, either by putting the ball into play more frequently or hitting it harder.

—–

That brings us into contact quality, where there isn’t a great answer. As with most high fastball pitchers, Dayton allows a ton of fly balls. That isn’t really a bad thing if he can keep getting a ton of strikeouts (it’s worked for Kenley Jansen so far), but it’s still worth knowing what happens when batters put the ball in play. Dayton allowed four regular-season homers and one post-season homer last season, and all came on the four-seamer. Five homers in fewer than 30 innings isn’t great. However, batters didn’t really do anything with the other four-seamers put into play, managing only six singles and one double during the regular season.

Contact quality stats are in a really strange place right now. There’s a lot of information available via StatCast and a still-developing way of knowing how to approach it. StatCast doesn’t track every ball in play (~90 percent capture rate) and there is evidence that what is captured has park effects. I can tell you that Dayton had the eighth-lowest average exit velocity on tracked four-seam fastballs put into play last year, but then sitting two spots below than him was Casey Fien, and we saw how those results treated him. Dayton also ranked very well when looking at velocity allowed on just fly balls, but I still don’t know what that means for the future.

Fly ball pitchers will always live on the tightrope between pop flies and 500-foot dingers. Dayton straddled that spectrum last year, allowing a lot of both. His long-term success is going to depend a lot on if he can suppress homers, and there just isn’t enough sample there yet to know if he will. Missing bats will help, too. The recent power spike in baseball, and questions on if and how it will continue, make answering that question even harder.

—–

So far, all that’s been described in this article is how Dayton’s four-seam fastball is great, but not why. Dayton doesn’t have amazing velocity. He doesn’t have above-average extension towards the plate. He has slightly above-average spin, but it’s not in the top 100. The best way to sum up how special Dayton’s fastball is is simply movement.

Dayton’s average four-seamer had 11.26 inches of vertical rise last season, which was 18th-best in baseball. The pitch averaged slightly more than six inches of run as well, which was 109th of 385 pitchers with at least 200 four-seamers. That doesn’t sound like much, but above-average movement in one axis combined with very good movement in the other combines to elite movement overall. Dayton’s four-seam had the ninth-most total movement in baseball last season. Dayton’s fastball was faster than the eight names above his.

—–

Add it all up, and Dayton’s four-seam fastball was incredible, one of the very best in all of baseball. Dayton’s success last season came in small sample size in terms of innings pitched (just 26 1/3), but the high pitch usage helps offset that. No wonder Dayton’s use of the fastball increased in every month of the regular season. The pitch may not be quite so good to make him a one-pitch pitcher like the man who will pitch in the inning after him this season, but it more than makes up for his iffy secondary options. As long as Dayton maintains his control and can keep getting batters to flail at that incredible fastball, he won’t have any trouble repeating last year’s success.

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog