About a week ago, Jon Weisman sent out a tweet from the Dodger Insider account talking about how shifts aren’t as hot a topic among fans or the media this year in regards to the Dodgers.

Watching 3B Justin Turner field a ball hit right at him in short RF, I feel complaints about shifting have really diminished, which is good.

— Dodger Insider (@DodgerInsider) September 6, 2016

I noticed the same, and I made an off-hand comment about how new third base/infield coach Chris Woodward seems to have had more success with his shifts than the previous regime did.

https://twitter.com/ChadMoriyama/status/772957649683947520

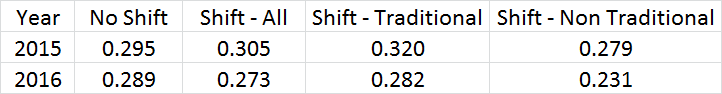

Like I mentioned, though, it was just an anecdotal observation of how it felt while watching every game. But instead of relying on that, I thought I’d take a look at the actual numbers to see if they backed what I observed.

As Of 9/10

The results appear to speak for themselves at this point. Last year, the Dodgers last year were significantly worse at getting outs on balls in play when they shifted than this year. In fact, a lot of the time the Dodgers were worse last year while shifting that not, but now there’s a considerable improvement from their typical alignment. The gap between past and present is largest when accounting for positional shifts that don’t rely on overloading one side of the infield, which should hypothetically reflect the subtleties of understanding a hitter’s spray chart combined with the pitcher’s stuff and how the team wants to attack the hitter. It’s an impressive and dramatic improvement.

That’s not to say it’s flawless, of course. I use a lot of qualifiers because there’s room for error in things like luck, along with other factors. That said, it’s almost the end of 2016 already. As such, the sample’s almost as large as it can get for year-to-year comparisons, and what it reflects is a defense that’s far better positioned to record outs when shifted out of their traditional positioning.

Then again, Woodward finding ways to make concepts work shouldn’t surprise given his open-mindedness and desire to get results.

“The beautiful thing about the Dodgers,” he says, “is that we have a lot of forward-thinking people who aren’t afraid to step outside the box a little bit when it comes to maximizing performance.

“From a game-management standpoint, I love hearing people’s ideas. And we’ve got all these numbers nowadays—analytics—and they reveal a lot of flaws in traditional baseball thinking: playing outfielders shallow as opposed to deep, the infield shifts, all that stuff. It makes sense. I love it.”

And perhaps the best part is that he doesn’t just shift for the sake of adhering to a basic analytics dogma, but appears to merge his baseball knowledge with the numbers.

Woodward, the new architect of the Dodgers’ shifts after two years in Seattle, doesn’t obey Kershaw’s spray chart religiously. He’s seen too many shifts backfire.

Woodward said his infielders shift less often with Kershaw on the mound compared to any other pitcher on the Dodgers’ staff.

Merging his existing knowledge of baseball, what his own players communicate to him, and what the numbers say in an attempt to get the best possible result is always a solid plan when it comes to baseball. And fortunately for the Dodgers, the team gets to reap the benefits of his work.

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog