We’re starting to get to the point of the season where a team’s cohesive pitching strategy comes into view. It’s still early, and that strategy is dependent on the personnel on the team, but the Dodgers have made a few changes to how they pitch this year which seem meaningful and potentially extends beyond who they have on their roster.

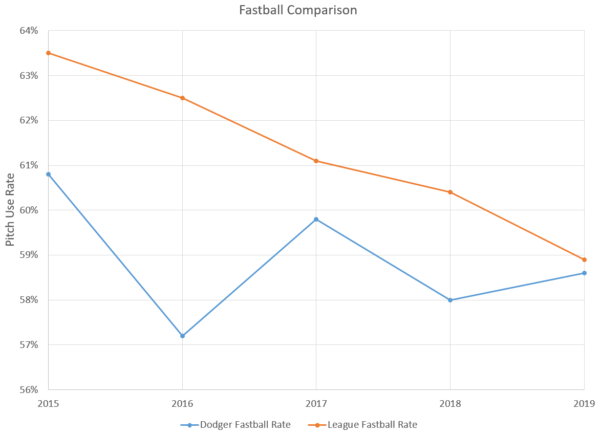

Over the last few seasons, the league-wide fastball rate has trended downward. This makes sense given that outings are shorter in general. Swing-and-miss rates are higher on non-fastballs, and shorter pitching stints reduce the need to establish the fastball. The Dodgers have been at the forefront of this trend, posting some of the lowest fastball rates in baseball over the past five seasons. However, this year, things have changed:

The league has caught up to them. Some of this is personnel-related. Clayton Kershaw and Ross Stripling throw fewer fastballs than most other starters, and they’ve pitched a smaller share of innings than they did last year. Alex Wood had one of the lowest fastball rates among starters last year and now he’s in Cincinnati. More innings are going to pitchers who throw more fastballs.

Most of the Dodgers who were on the team have not changed their fastball usage dramatically. Hyun-Jin Ryu has added a sinker, but mostly at the expense of his fourseamer (his overall fastball rate is up 4%). Walker Buehler is throwing a lot more fourseam fastballs this year, but mostly at the expense of his sinker. A lot of little changes have added up to a staff-wide average that is almost identical to the league average. While this is different from previous years, it’s a little hard to see an organization-wide shift.

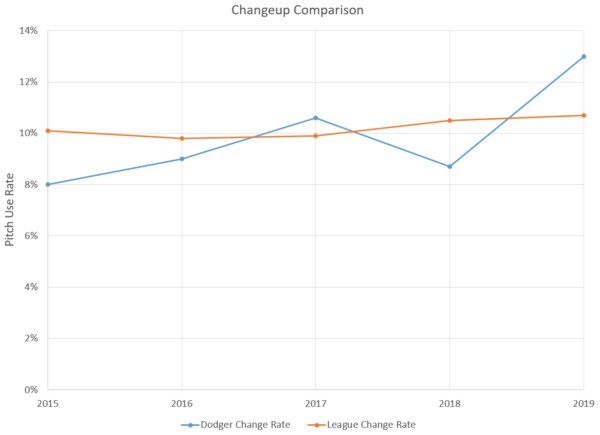

However, some more extreme changes are visible when looking at the Dodgers’ off-speed usage, particularly with change-ups:

The Dodgers are throwing changes more often than they ever have since PitchInfo began tracking pitch usage in 2007. They’re still only 8th in the league in change usage this year — when Buehler and Kershaw never throw the pitch the rate will only go up by so much — but it’s still a significant departure from prior seasons. This massive uptick can be traced to three pitchers in particular.

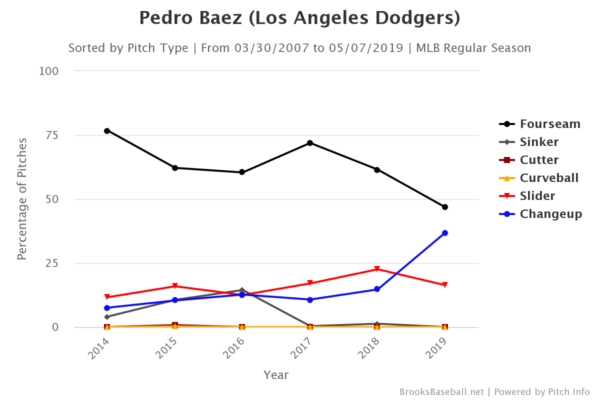

The first, and the primary success story, is Pedro Baez. Baez found his change last season and used it to fuel a late-season hot streak, as I detailed in The Athletic last year. This season, it’s an even more trusted weapon:

Baez’ change has lost some sink but added some fade this year, and the result seems to be fewer swings and misses (among the 52 pitchers who have thrown 100 changes, he is 24th in whiffs per swing). However, the changeup has added a new dimension to his pitching ability, which allows his fastball to play up. He’s a much less predictable pitcher now, and the results have really shown.

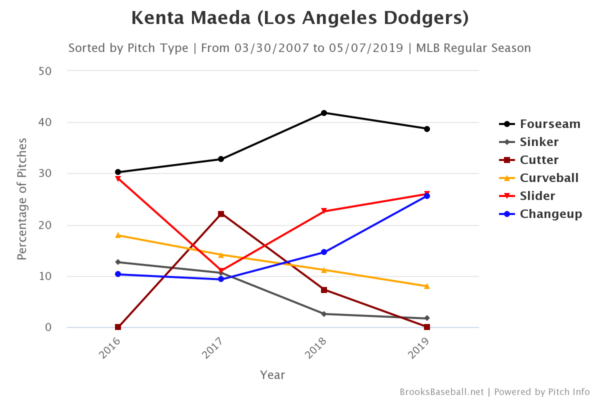

The other two pitchers with dramatic change usage rate differences are not success stories. Kenta Maeda introduced a fosh-grip change to his repertoire last season, and it paid immediate dividends. At the All-Star break, his change was one of the single best pitches in baseball. It looked like the solution to what used to be his biggest problem as a starter: getting left-handed batters out.

Batters are making significantly more contact against Maeda’s change this year, but it hasn’t been his big problem. His change has been his best pitch in terms of batting average allowed, slugging allowed, and whiff-per-swing rate (excluding his curve, which he isn’t throwing much). The problem is more that the change is the only pitch of which he has any sort of command. Batters are slugging .750 against his fastball and taking advantage of the increased number of changes in high-leverage situations. The change has probably kept Maeda from being completely unplayable this year, but it could be making him too predictable, the opposite of the gains Baez has made.

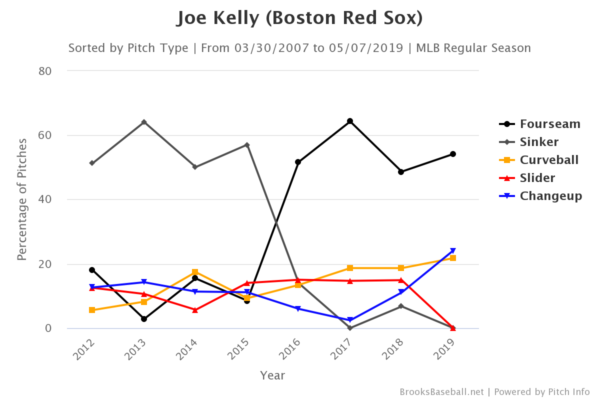

The other Dodger who has increased his changeup usage, and the one who can potentially reveal that this is at least somewhat of an organizational philosophy, is Joe Kelly. Kelly has been an absolute disaster this year, so he might be evidence that this new pitching strategy isn’t working. Kelly is throwing changes much more often than he has at any point in his career, even during the playoff run which enamored the Dodgers so much:

Kelly has essentially shelved his slider in favor of more changes, and there is actually some evidence that this is a good idea. In 2019, Kelly’s change has been a ground ball when put in play 77% of the time, and it has the highest miss-per-pitch rate among his offerings. Batters hit it for less power than the fastball or curve.

However, the positive numbers on the change say more about how bad his other pitches have been: Kelly has allowed a .412 average on changes this year. Kelly’s awful command has meant that most of his results this year are more than bad fortune, though that is less true of his changeup than it is of his fastball or curve. That ground-ball rate might be telling of what the Dodgers see in the pitch, and potentially shows a path out of the incredibly deep hole that Kelly has dug for himself this season.

——

Overall, the Dodgers’ different pitching strategy this season seems interesting. The fastball use increase seems more like a blip rather than a significant change in strategy among individual pitchers (and could just be a difference between how Austin Barnes and Yasmani Grandal call games).

The changeup difference seems more real. In the case of Baez, increased trust in the change has led to a breakout, and now he’s one of the better relievers in baseball, a realization of the potential that took a frustratingly long time to reach. In the cases of Maeda and Kelly, it’s hard to say it has helped them that much. However, due to the results of their changes compared to their other pitches, it could also be said that their increased reliance on changes is saving them from having even worse seasons.

Either way, this is something to keep an eye on as the Dodgers begin to acquire pitchers. If those pitchers throw more fastballs or more changeups, we’ll gain more evidence that this is a real trend and a real departure from their previous philosophy. At this point, the evidence is at least somewhat tenuous, and the results are more than somewhat mixed.

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog