It’s a moment which will live in Dodger history forever. Walker Buehler fired a vicious curveball to former teammate Alex Verdugo, who feebly swung and missed as the pitch tumbled into the dirt. The Dodgers had won the 2024 World Series and were about to host the parade which provided motivation for their improbable run. Buehler raised his hands in the air as his teammates rushed around him. “Who else?,” he later asked on Instagram:

In his excellent story on the Dodgers’ series win, Jeff Passan dug into what that phrase means to Buehler:

“That’s how I feel about myself,” Buehler said. “Who else is going to do it? Who else is going to be out there? Who else is supposed to do this? We’ve got 30 guys that believe that same way. And I was just the one in the spot to do it.”

“Who else?” was also an extremely valid strategic question for most of that evening. The Dodgers setup Game 5 of the World Series like they had multiple others in the postseason, by playing the long game the night before. In using all of their low-leverage, bulk relievers the previous game, the Dodgers were ready to aggressively manage the new game in front of them, knowing that everybody could rest for the winter when the series was over. All they needed was a somewhat competent start from Jack Flaherty, and they had six relief pitchers they were comfortable using in any leverage situation afterwards.

However, Flaherty imploded. The Dodgers had 23 outs left to bridge. Even worse, several of the leverage pitchers the Dodgers would normally depend on to get more than three of those outs were not effective enough to do so. Anthony Banda was uncharacteristically wild, walking two batters en route to two outs. Alex Vesia needed 23 pitches to get through his inning, and the typically efficient Brusdar Graterol needed one more pitch than that to record two outs. By the end of the eighth inning, the six relievers the Dodgers planned to use to lock down the season allowed 13 baserunners (including eight walks and one hit-by-pitch) and threw 135 pitches in less than seven innings of work.

As the Dodger bats took advantage of the Yankee defense’s self-immolation and brought a lopsided game towards one which was winnable, only Blake Treinen’s gutsy performance kept the pitching plan from unravelling completely. However, after seven outs, he had given all he had. “Who else?” was the question on everybody’s minds. The only regular relievers theoretically still available were Daniel Hudson, who allowed four runs the night prior and whose elbow was disintegrating in the bullpen, and Ben Casparius, who threw 43 pitches in that same game. There was no other answer to “Who else?” It had to be Buehler.

Buehler’s first opposing hitter in his bid to close out the World Series was Anthony Volpe. His first pitch, a four-seam fastball, missed its spot by three feet. It looked like a return to wildness against a Yankee lineup which spoiled the Dodgers’ best-laid plans with their disciplined approach. They looked poised to use Buehler’s adrenaline against him. Juan Soto and Aaron Judge were due up fifth and sixth and would have the winning run on base in front of them if they reached the plate. Buehler could not afford to issue another walk; he had to find strikes quickly. His second pitch to Volpe was a two-seam fastball, which clipped the outside corner. Then he fired his third pitch, the same pitch he’d go on to use to win the World Series.

——

The phrase “Who else?,” while being a perfect encapsulation of Buehler’s legendary self-confidence, betrays the fact that he had to go through hell to be the answer in this moment. For most of the past three seasons, and particularly for most of 2024, it looked like it could, or should, have been anybody else.

The road to Buehler’s re-ascent began, naturally, while he was still on top. In 2021, Buehler finished fourth place in Cy Young voting, thanks to leading the league in both park-adjusted ERA and games started. It was the breakout season everybody knew was coming, a culmination of his rise to Dodger stardom. However, despite the fact that his career-altering injuries didn’t begin until the next season, the harbinger of his difficult return arrived that June.

That month, MLB began cracking down on the use of foreign substances used by pitchers to influence pitch spin. It was an open secret that Buehler was using pine tar (or something similar) to add spin on his pitches, just the like the vast majority of other pitchers in the league. Social media was full of jokes about Buehler looking like he bathed in the stuff during his 2020 playoff starts. He was far from alone in this transgression, and the league announcing that they were going to have umpires more rigorously check pitchers was going to impact him.

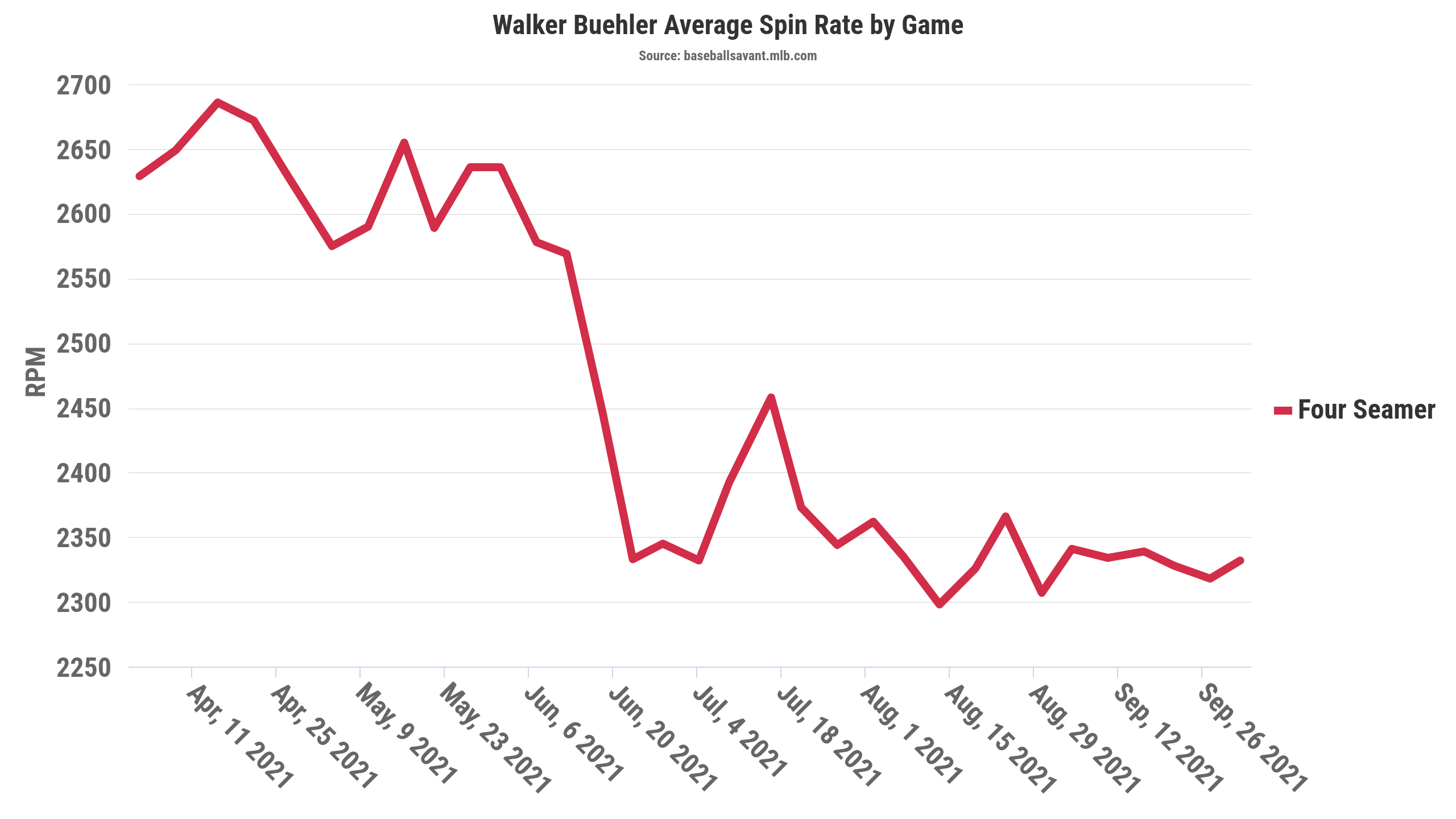

As expected, Buehler lost a lot of spin when MLB began enforcing their rules, as did most Dodger pitchers and most pitchers league-wide:

Surprisingly, this change didn’t impact Buehler’s performance very much. Buehler’s ERA before the league’s foreign substance checks began was 2.38, and his ERA after was 2.54. His strikeout rate hardly changed. The effects of the substance crack-down were more subtle than that.

Buehler had to change how he pitched (substantially reducing his four-seam fastball use rate) after the league enforced their pre-existing rules, and the raw ingredients of his pitches worsened. Buehler’s four-seam fastball Stuff+ (FanGraphs model) was 150 in 2020, which reduced to 115 over the full course of 2021, and was down to a below-average 80 before his injury in 2022. Buehler also lost fastball velocity, which can correspond to spin loss, but that drop occurred months before the foreign substance crackdown began.

In the months and years following the league’s new enforcement of their foreign substance rules, many pitchers began to find (potentially disallowed) ways to add more spin, but Buehler’s spin rates remained stubbornly at their low levels. If things started to go wrong and he had to tinker with mechanics or usage to solve efficacy problems, the foundation was less stable than it previously was. Buehler spent his 2022 season toiling in maddening mediocrity, also impacted by his worsening elbow problems. In August, he underwent his second Tommy John surgery and missed all of the following season.

During 2024’s regular season, Buehler was not able to find the form he lost due to injury and reduced spin rates, though he was tantalizingly, frustratingly close to the pieces coming together at times. The way this most clearly manifested was in his inability to put batters away after he reached two strike counts. Batters had a .767 OPS against Buehler after he reached two strikes during the regular season, twice as high as the league’s OPS in those situations. Buehler’s OPS allowed with two strikes was higher than Will Smith’s overall OPS this season. In 2021, when Buehler was on top of the world, he allowed a .417 OPS with two strikes.

Still, Buehler retained a rotation spot by default down the stretch as the pitching staff crumbled around him. His regular season performance didn’t really merit a postseason roster spot, but the presence of a healthy right arm did. It’s fair to wonder if Buehler would have been rostered at all if not for the late-season bad news on Gavin Stone’s shoulder and Tyler Glasnow’s elbow. Would the Dodgers have left Buehler off the roster entirely in favor of running bullpen games, like they did with Bobby Miller (more on him from Josh tomorrow)? The world will never know; the Dodgers are better off for not knowing.

“Who else?” At this point, like there would be in a month, there was nobody else. The roster spot was Buehler’s, and the Dodgers’ postseason success would hinge upon his ability to figure things out. Adrenaline had helped him before.

——

Buehler’s first playoff start, Game 3 of the NLDS against the Padres, contained many of the frustrations which spoiled his regular season. While his overall line was severely blemished by the Dodger defense’s own self-immolation, his inability to put away batters worsened it. Buehler induced eight swings and misses in that game — an above-average whiff rate for his season against a high-contact offense would normally be a good result — but none of them came with two strikes. He ended the day with no strikeouts. However, Buehler managed to pitch three quality innings after the Padre second inning rally, which set the Dodger bullpen up for a successful full-length bullpen game the following day. Even in a bad start, Buehler had a small victory to build on.

That small victory grew larger in Buehler’s NLCS Game 4 start against the Mets. Buehler threw four scoreless innings while inducing 16 swings and misses, his most in a game since his last regular-season start of 2021. The outing was far from perfect — his spray pattern was less of a pattern and more of a fire hose of random locations — but he did more than what the team needed from him.

Mechanically, Buehler pitched from the stretch even with no runners on, but more important was that his pitches had more movement than usual, despite not corresponding with a substantial increase in overall spin. This extra movement was most dramatic in the pairing of Buehler’s knuckle-curve and his four-seam fastball, used here to strike out Francisco Lindor in the biggest spot of the start, if not the entire series:

BUETANE. pic.twitter.com/brX00gV4Ee

— Los Angeles Dodgers (@Dodgers) October 17, 2024

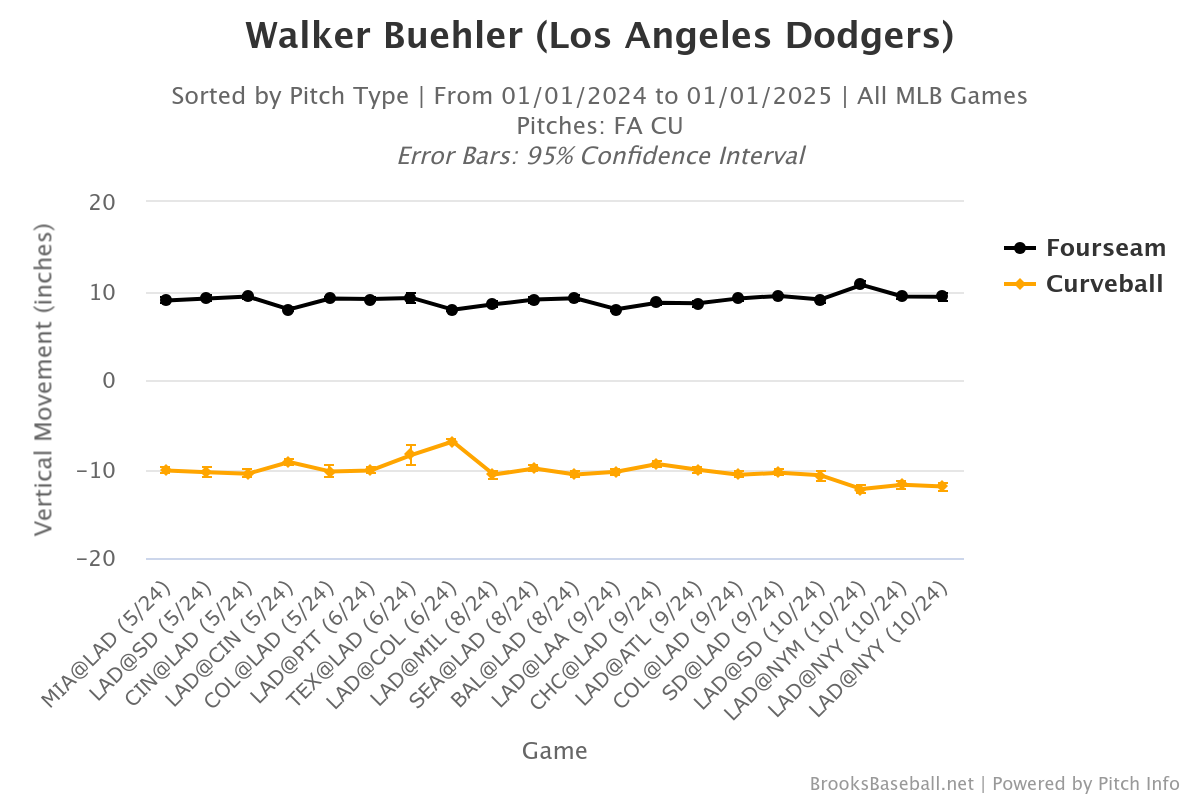

Throughout most of 2024, and since Buehler’s curve lost spin in 2021, the pitch generally averaged about 10 inches of vertical drop relative to a spinless baseball. Buehler’s 16 curveballs against the Mets dropped an average of 12 inches.

Buehler’s curveball has gained importance as his career has progressed. One hallmark of his breakout in 2021 is that he split his traditional slider into a sweeper-cutter pairing. He uses the sweeper against right-handed batters and the cutter against lefties, very rarely deviating from that pattern. This places extra importance on the curveball to left-handed hitters, since it is his only real tool to throw a pitch slower than 90 MPH against them. When a left-handed batter swung at Buehler’s curve in the 2024 regular season, they missed 27% of the time, a pedestrian rate, but the best rate he had available. He responded by throwing more curves in 2024 than he had at any other point of his starting career. And now, in the NLCS, that curve found another gear.

In his post-game interviews, Buehler suggested the cold weather and wind as a potential sources for his success. The temperature at first pitch in his NLCS start was 51 degrees, dipping into the 40s by the time Buehler’s night was done. Buehler was not the only other pitcher who found movement in the cold environs of Citi Field:

Movement is up for the third straight game in Citi, for most pitchers. Talked about it on @ratesandbarrels today… some guys have *slightly* higher spin but most have more movement. I think it’s the cold weather, maybe salt in air, both would increase drag & movement. Maybe wind.

— Eno Sarris (@enosarris) October 18, 2024

Thankfully then, Buehler’s next start, his excellent outing in World Series Game 3, was also in the cold. The game-time temperature was only one degree warmer than it was in Queens the prior week. However, Buehler did not achieve as much success in that game with his curveball. He threw it a lot — 19 of his 76 pitches — but he lacked the command necessary for good results. He only generated one swing and miss with the pitch, finding his success on other offerings instead.

Even though the curve wasn’t integral to Buehler’s success in Game 3, one ingredient did carry over from his NLCS start against the Mets: the still had extra movement, despite it disappearing from his other offerings.

Note: Vertical movement of Buehler’s four-seam fastball and curveball in every game of 2024. Observe the spikes in the third-to-last point (Mets NLCS start), and that the curve retains the extra movement afterwards.

This was about to become extremely important.

——

Two days later, with Game 5 of the World Series on the line, the Dodgers had to ask “Who else?” once again. The cold would not back up Buehler now — the game-time temperature for Game 5 was 15 degrees warmer than it was two days prior. After his first two fastballs against Volpe, Buehler and Smith decided to find out how the warmer weather would impact the curve:

— Daniel Brim (@DanielBrim) November 3, 2024

The pitch’s movement was as sharp as it was against the Mets, and as well-placed as any he threw against the Yankees in Game 3. The relief adrenaline was helping the pitch, not causing it to escape to the glove-side like his four-seamer. Two pitches later, after missing badly with another adrenaline fastball, Buehler threw a second curve. The location was a mistake, in the upper part of the zone, but the extra movement helped the ball spin below the barrel of Volpe’s bat instead of directly into it. Volpe grounded to third base, and the Dodgers were two outs away.

The next batter to stand between Buehler and history was Austin Wells, the Yankees’ left-handed hitting catcher. Left-handed batters were a more natural fit to how Buehler used the curveball in 2024, and Buehler was feeling good with the pitch after dispatching Volpe. Wells and Buehler battled to a 3-2 count. Four of the six pitches Buehler threw on the way were curves, the other two were missed locations with his four-seamer. During the regular season, Buehler struggled badly in full counts, allowing a 1.095 OPS while walking 19 batters and striking out just 12, the poor numbers emblematic of his problems finishing off opposing hitters. The difference between an out and a baserunner in this situation was the difference between Verdugo — who had already hit a two-run ninth-inning homer in the series — representing the winning run or hitting with the bases empty. Buehler threw the payoff pitch:

— Daniel Brim (@DanielBrim) November 3, 2024

One out to go. Verdugo stood between Buehler and history. Seven of Buehler’s previous ten pitches had been curveballs. On paper, Verdugo was a tough assignment. Buehler was in swing-and-miss mode, a place he hadn’t been for most of the season, and Verdugo is a very difficult batter to strike out. Against right-handed pitchers, Verdugo only swung and missed at 7% of the pitches he saw this season, which placed him in the 90th percentile among the league’s left-handed batters. Additionally, Verdugo could eliminate Buehler’s four-seam fastball (and the peak of his velocity) from his mind, given the curveball-heavy approach and that Buehler was repeatedly missing to his glove-side with the four-seamer.

Buehler started the plate appearance predictably, with a curve. The pitch was well-located, but Verdugo, who was expecting it, took it just below the zone for a ball. Buehler then finally deviated from his pattern with a cutter inside, which fooled Verdugo badly. Verdugo’s swing revealed that he wasn’t necessarily sitting on the curve — a curveball at this swing decision point may have hit his back foot — but that he was jumpy and over-eager to pull the ball. That was all Buehler needed to do to go back to what was working best. Verdugo swung over 1-1 and 1-2 curveballs to end the game.

WALKER BUEHLER CLOSES IT OUT! #CHAMPS pic.twitter.com/1S2242udt6

— Los Angeles Dodgers (@Dodgers) October 31, 2024

10 of Buehler’s final 14 pitches to end the World Series were curveballs. He generated three swings and misses with the pitch, which would have ranked third amongst his regular-season starts. Again, the pitch was not aided by extra spin, but the movement, shape, and locations were just right. The pitch he found in the cold a week prior worked in the warmer weather too, and the Dodgers won the World Series behind it. Buehler raised his arms to triumphantly ask, “Who else?”

——

Less than 48 hours after Buehler fanned Verdugo and Joe Davis commanded Los Angeles to start their party, Buehler found himself at its center. He donned a 1988 World Series game-worn Orel Hershiser jersey, loaned to him at the start of this playoff run. The jersey symbolized Buehler’s status as the heir apparent to Hershiser’s “Bulldog” moniker, a fierce presence on the mound who commanded the game instead of letting it happen to him. Buehler’s struggle to find his form in the regular season often felt too much like the latter. A month later, the jersey couldn’t feel more appropriate.

During the Dodgers’ parade, Buehler drank beer from a funnel, drops of it escaping onto the jersey. On the broadcast of the celebration, Hershiser seemed amused, stating that the beer was now as much a part of the garment’s history as his heroics in it 36 years prior.

Who else but Walker Buehler? There is nobody else.

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog