Just over a third of the way into the 2024 season, the top of the Dodger rotation has been one of their biggest strengths. The high-profile additions of Tyler Glasnow and Yoshinobu Yamamoto have both paid dividends, both proving to be important pieces as injuries have pressured the team’s starting depth. They’ve been who the Dodgers pictured them to be. However, neither are leading Dodger starting pitchers in ERA since the last week of April, nor are they even close. That honor belongs to Gavin Stone and his 1.64 mark over his last seven starts.

Stone’s season has been remarkable, especially given his early tenuous status in the rotation after a rough 2023 and a bumpy start to 2024. Stone’s peripherals are not quite as nice to him as his shiny ERA, but when digging deeper, those numbers still look like ones which belong to perfectly good number three starters. In short, Stone looks like a completely different pitcher than he did last year. Other than mechanical adjustments to alleviate a well-documented pitch tipping issue, the biggest difference between 2023’s Gavin Stone and 2024’s Gavin Stone has been his pitch arsenal.

——

Stone entered the league with what could be classified as a three pitch mix — a four-seam fastball, a slider, and his primary weapon, the change. He would also mix in a curveball once or twice per game, but not often enough to be a major consideration for batters. By the end of the season, Stone had started to throw a two-seam fastball as well, but his arsenal still had a major flaw — one which can be an issue for change-heavy pitchers: reverse platoon splits.

In 2023, right-handed batters hit .351 and slugged .649 against Stone. Lefties still hit him hard but the numbers were slightly less dramatic (.322 and .542, respectively). A major factor in these reverse splits was Stone’s pitch selection. Many pitchers are uncomfortable throwing change-ups to same-sided batters because they can break directly into their swing paths. While Stone doesn’t eliminate changes entirely against right-handed batters, the usage difference was significant. Last season, more than half of the pitches Stone threw to left-handed batters were changes. Against right-handed batters, that rate was cut in half.

Stone was carried by the change in the minors, but his major weapon just wasn’t working at the top level and wasn’t seeing much use against the majority of the batters he faced. Stone’s pitch usage against right-handed batters raised concerns about his ability to turn over lineups, which in turn raised questions about his ability to remain a starting pitcher. He needed a new tool, and this season he has found one: his slider.

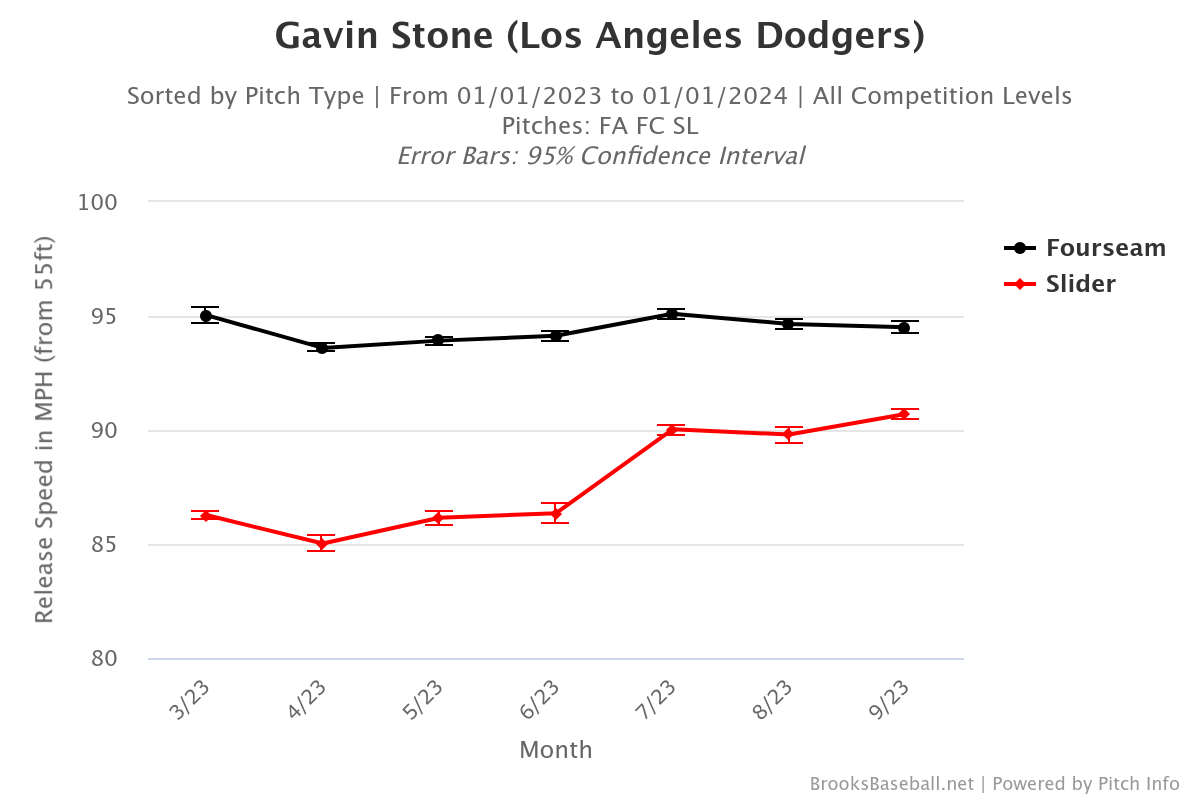

The evolution of Stone’s slider began last season. Between his demotion in May and his promotion back to the majors in July, his slider went from averaging 86 mph to averaging just over 90:

However, the increase in velocity came at the expense of depth: Stone’s slider dropped about eight inches relative to his four-seam fastball in April and May, but that number was below five by the end of the year. The new slider also had less horizontal run, so it didn’t have much to keep it off the barrel. In the 23 plate appearances which ended with a Stone slider after he was recalled, batters averaged .391 and slugged an almost unbelievable .870.

One year later, Stone’s slider has been one of the keys to his breakout first half. Per FanGraph’s Stuff+ metric, Stone’s slider has been his best pitch this season by a wide margin — a 128 value in this metric is similar to Glasnow’s curveball and is higher than any pitch Yamamoto has shown this season. When batters have swung at Stone’s slider this season, they have missed 43% of the time, which is in the top 20% among pitchers who have thrown 100 sliders in 2024. The results on balls in play have shown a remarkable turnaround: batters are both hitting and slugging .243 in plate appearances ending with Stone sliders this season (Stone has been a bit lucky here as well — his xwOBA on the slider is near league average — but it still represents a huge step up from 2023 when the pitch was barely usable).

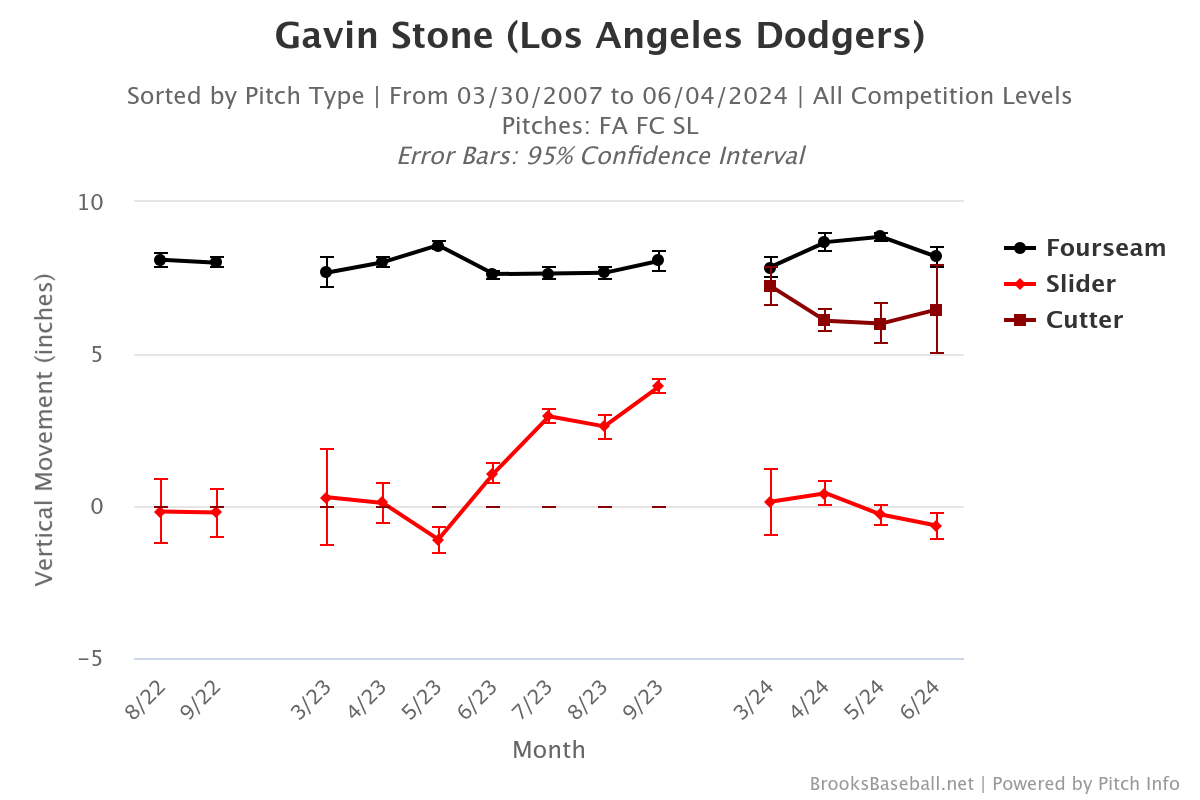

The changes which Stone made to his slider this season reflect his desire to improve his previously-abysmal results against right-handed hitting. The pitch has changed in shape, velocity, and use pattern, all of which help against right-handed batters. Essentially, Stone has created two different pitches building from the base of his late-2023 slider, and he uses them very differently depending on which side of the plate his opponent is standing on.

122 of the 130 sliders Stone has thrown this season have been to right-handed batters, only trailing his four-seamer in overall usage against same-sided hitters. This new version of the slider moves similarly to the 86 mph slider he entered the league with but is thrown much harder, averaging around 89 so far. It moves like his softer slider, but it’s thrown like the harder one.

Hello, here is a video of a Gavin Stone slider pic.twitter.com/kuVL4S4Huh

— Daniel Brim (@DanielBrim) June 5, 2024

As Stone has reduced the number of sliders thrown to left-handed batters this season, he has replaced it with a new cut fastball. This cutter has less drop than last season’s hard slider (which allows it to be effective higher in the zone), but it is also thrown much harder, averaging around 93 mph. During his recent hot streak, Stone has exclusively thrown the cutter to lefties, and his catchers are willing to ask for the pitch both high and low.

Splitting the slider and cutter into two pitches and throwing them based on batter handedness has allowed Stone to find a shape and velocity which works best for each situation. This cutter wouldn’t work well against right-handed batters, but it’s perfect for working on the hands against lefties. This slider wouldn’t work well against lefties, but now he has a less dangerous breaking ball to throw to his fellow right-handers. The ability to do tailor use like this and retain feel for both pitches is extremely difficult to do, but Stone has been making it look easy over the last six weeks.

Hello, here is a video of a Gavin Stone cutter pic.twitter.com/aV3lo4p3RM

— Daniel Brim (@DanielBrim) June 5, 2024

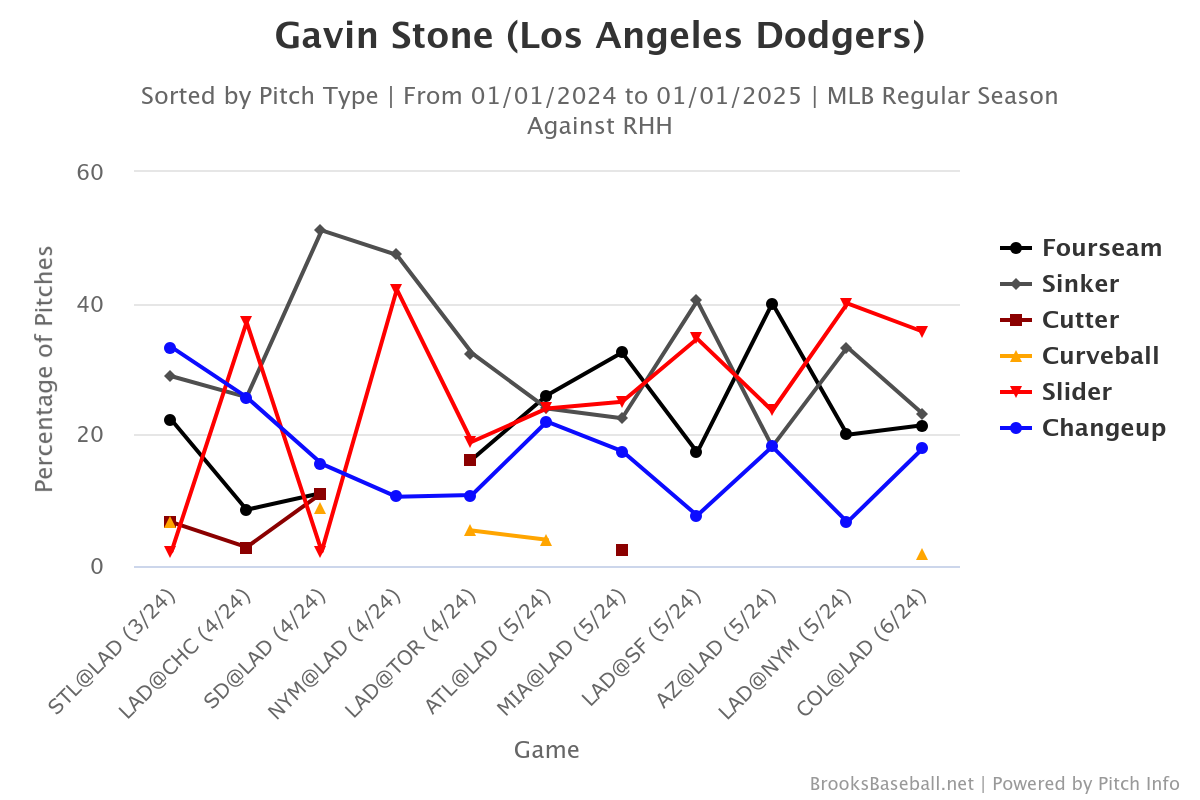

Stone has been responding to the success of his slider by throwing it more as the season has progressed. In each of his last two starts, the slider has been his most-thrown pitch to right-handers, with usage rates of 40% and 35%. During this hot streak, he has trusted the pitch more and more:

This is one reason why Stone’s swing-and-miss numbers have been increasing as the season has gone on; in his last 12 innings, Stone has struck out 13 batters. A lack of swing-and-miss is one of the factors which could lead to Stone regressing, so adjustments to bring out more whiffs are welcome and necessary.

——

While Stone’s numbers will likely come back to earth a bit, his excellent season has been more than luck. The evolution of his slider is just one example of how he’s rapidly become a much more complete pitcher, and how hard he’s had to work to get here. When Stone arrived from the minors a little more than a year ago, he was a three-pitch pitcher, relying on stuff more than command. Now he throws six pitches, and his most effective weapon has been completely revamped. His command has looked significantly sharper as well.

Last season’s struggles were Stone’s first real taste of adversity as a professional, and now he’s on the other side significantly better for it. This ability to adapt is one of the key characteristics for a player who can stick in the majors for a long time to come.

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog