When Sergio Romo makes his first appearance for the Dodgers this year, he will become the 226th player in MLB history to have played for both the Dodgers and the Giants. That’s a lot of players, and a reminder that no matter how much stock fans may put into the rivalry between the two teams, baseball is first and foremost a business, and first and foremost a job for these guys.

That said, the Dodgers and Giants don’t do business together all that often. In the entire history of the two franchises, they have completed just ten trades, and only three since the teams relocated to the west coast. Two of those trades are featured in this segment. (There are also examples of the teams selling players to each other, which, while not considered a trade in the context of the day, is akin to trading a player for cash considerations.)

Since it would take far too long to go through everyone on the list, let’s just focus on some of the more noteworthy examples of Giants who became Dodgers. Today’s post covers the early days of the two franchises, the 1890s through the 1910s.

——

Years with Giants: 1883-1889; 1893-1894

Years with Dodgers: 1891-1892

Per the Dodgers, 1890 is the official first year of the franchise, as far as the team’s records go. While the franchise technically existed before then, 1890 was its first year in the National League. From 1883 until 1889, it belonged to the short-lived American Association (which existed from 1882 until 1891). An even shorter-lived organization was the Players’ League, which existed for just the 1890 season. That league is central to the story of how our first subject got from the New York Giants to the Brooklyn Grooms in the early days of the latter’s NL tenure.

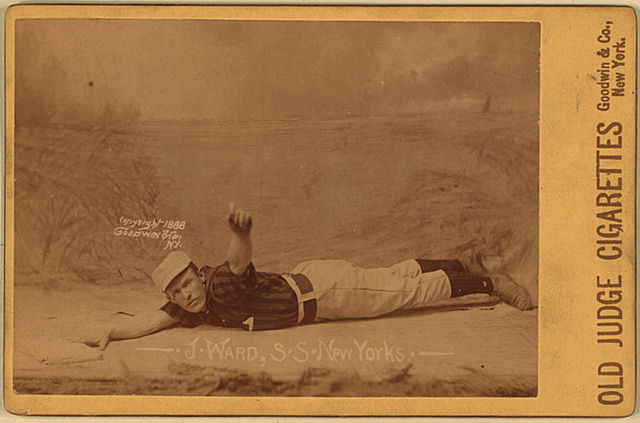

Hall of Famer John Montgomery “Monte” Ward, an especially fascinating figure in baseball history, began his career as a pitcher and enjoyed much success in that role. Ward threw one of just two 19th century perfect games, his coming on June 17, 1880 against the Buffalo Bisons (a mere five days after Lee Richmond of Worcester threw the first perfect game in MLB history). However, by 1883, Ward had completely transitioned to being a position player (primarily, a second baseman and shortstop).

In 1883, Ward was sold by the Providence Grays (with whom he spent his first five seasons) to the New York Gothams (as they were known from 1883-1885). His first several seasons with New York saw him perform adequately, though he was hardly the offensive superstar of any of those teams. That changed in 1887, when his .338 batting average — the prized statistic in those days — led the team. He was also an integral part of the 1888 and 1889 league champion teams. However, Ward grew frustrated with the treatment players received from the National League. In 1890, he decided to leave the Giants to develop a rival league.

The Players’ League, which aimed to put control into the hands of — you guessed it — the players, consisted of eight teams. Ward served as player-manager for the Brooklyn team, known as Ward’s Wonders. Ward, who had some previous managerial experience (having helmed the Providence Grays for 31 games in 1880 and the Gothams for 14 games in 1884), guided his team to second place. When the league folded, he transitioned to another Brooklyn team, the Grooms of the NL.

The Grooms did not do especially well under Ward’s guidance. They finished in sixth place in 1891, then (somewhat) improved to a third-place finish in 1892. Ward’s performance on the field, though, was respectable enough. He served as the Grooms’ regular starting shortstop in 1891, and as their regular starting second baseman in 1892.

The following season, Ward requested to return to the Giants, and was sold back to them. He finished off his playing career with two seasons as their player-manager; they finished in fifth and second place, respectively.

In retirement, Ward attempted to launch yet another rival league, the Federal League, which lasted from 1913 to 1915.

A few additional notes about Ward (whose entire SABR biography is worth reading):

- While still playing baseball, Ward earned both a law degree and a political science degree from Columbia.

- Ward was responsible for founding the first players’ union, and long advocated for player rights.

- Ward attempted to racially integrate the National League in 1887, according to his Hall of Fame biography.

Years with Giants: 1903 (Babb); 1903 (Cronin)

Years with Dodgers: 1902-1903 (Babb); 1895; 1904 (Cronin)

Infielder Charlie Babb and pitcher/outfielder Jack Cronin get mentioned for one reason and one reason only: they were the Superbas’ return in the first-ever trade between the Giants and Dodgers franchises. In exchange, the Giants got veteran infielder Bill Dahlen.

Babb batted .248 in 502 plate appearances for the Giants; he batted .241 in his two seasons with Brooklyn. Cronin began his career with Brooklyn in 1895, but only made two starts. He played for four different teams before landing with the Giants in 1902. When he returned to the Superbas in 1904, he had a rather dismal win-loss record of 12-13; of course, that Brooklyn team also went 62-91 and finished 6th in the National League, so Cronin was hardly their only problem.

Years with Giants: 1905

Years with Dodgers: 1905

Infielder/outfielder Bob Hall isn’t a particularly notable ballplayer. He only played two Major League seasons, the second of which was split between the Giants and the Superbas (though he played just one game with the former). However, it wasn’t a trade that sent Hall from Manhattan to Brooklyn — it was a loan.

The idea of loaning a player is not unheard of in professional sports. It is fairly common in soccer. But it seems weird to think that it was something that happened in Major League Baseball. Honestly, this is the first I’ve heard of it, and I can’t seem to find any information on how it worked/how long it was allowed for. If anyone reading this knows more than I do, feel free to share, because I’m genuinely interested.

After completing the season with Brooklyn, Hall was sent back to the Giants, who then sold him to the Baltimore Orioles of the Eastern League. He played six more years of minor-league ball before retiring following the 1911 season.

Years with Giants: 1908-1915

Years with Dodgers: 1915-1920

Hall of Fame pitcher Rube Marquard began his career in the American Association, where he played for nearly three full seasons. In 1908, his contract was purchased by the Giants for a then-record $11,000. His first few seasons with New York were underwhelming, but he had a great run from 1911 through 1913, posting upwards of 20 wins each year (and I know how most DoDi readers feel about pitcher wins, but those were very important in the context of Marquard’s day).

After a less successful 1914 campaign and an unsatisfactory start to 1915, Marquard requested the Giants, who were en route to a last-place finish, grant his unconditional release. The Giants refused, and instead placed him on waivers. When he passed through unclaimed, the Giants sold Marquard’s contract to the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League — a minor league.

Marquard did not want to go to the minors, and initially threatened to go to Ward’s rival Federal League. However, he instead got in touch with his old mentor, Wilbert Robinson, now manager of the Brooklyn Robins. The Robins agreed to pay the requisite waiver fee, and Marquard officially joined the Brooklyn squad.

Marquard appeared in six games for Brooklyn in 1915, then played five seasons with them, including for the 1916 and 1920 pennant-winning teams. His first two full seasons were very good. What followed was a lackluster 1918, and a 1919 season that was shortened when Marquard broke his leg. His return in 1920 yielded reasonably good results, but his career with the Robins came to a fairly abrupt end. His SABR bio has the bizarre details:

Before Game Four a Cleveland undercover policeman arrested Marquard for attempting to sell his box-seat tickets. The judge, believing that the negative publicity was punishment enough, fined Marquard only $1 and court costs, for a grand total of $3.80. Brooklyn owner Charles Ebbets wasn’t as forgiving; on December 15 he traded Rube to Cincinnati for Dutch Ruether.

Marquard played with Cincinnati for a year, his last winning season. He closed out his career with four seasons in Boston.

Years with Giants: 1908-1915 (did not appear in any games in 1908)

Years with Dodgers: 1916-1917

John Tortes “Chief” Meyers was a Mission Indian from the Cahuilla tribe. He was nicknamed “Chief,” as many Native American ballplayers were, because folks in the early 20th century were not especially creative. A quick aside, from Baseball Almanac’s entry on American Indian baseball players:

There are fourteen former ballplayers who were either commonly called “chief” or simply nicknamed “chief” and in the Encyclopedia of North American Indians they wrote, “It is worth pointing out that while American Indian ballplayers were nearly always called ‘Chief,’ this nickname was used much less often among Indians themselves. John ‘Chief’ Meyers, for example, a Mission Indian who played against Chief Bender, referred to him as Charlie.”

Meyers spent most of his twenties playing in an assortment of places, including semi-pro ball in the southwest, and for Dartmouth’s team for a year. He didn’t actually play in a major league game until the age of 28. When he signed with the Giants, he became catcher for a pitching staff that included Christy Mathewson, with whom Meyers developed quite a rapport (seriously, the two did vaudeville together).

In addition to being a well-regarded catcher, Meyers had several excellent offensive seasons for the Giants, leading his team in batting average for three consecutive seasons (including the pennant-winning teams of 1911 and 1912). Meyers started to show signs of slowing down in 1915, his age-34 season (although per his SABR bio, he lied to his employers about his age). The Giants subsequently placed him on waivers, and he was claimed by both the Brooklyn Robins and the Boston Braves. According to the New York Times, the dispute was settled by a literal coin toss between the teams’ owners:

There was some lively bidding for the services of Chief Meyers, the veteran backstop of the Giants. The New York club asked for waivers on the Indian and Brooklyn and Boston both refused to waive. Yesterday Charles H. Ebbets of the Brooklyn and Percy D. Haughton of the Braves tossed up a coin to see who would get the catcher and Mr. Ebbets won the toss and got the Indian.

(Ah, 1916, when newspapers would just refer to a Native player as “the Indian.”)

The 1916 Robins won the National League pennant, though Meyers’s own offensive contributions were subpar.

Meyers played 47 games with the Robins in 1917 before he was traded to the Braves, where he finished his major league career.

Years with Giants: 1907-1916

Years with Dodgers: 1916-1917

Fred Merkle is, perhaps unfairly, best remembered for something that happened during his rookie season. Merkle’s Boner, as it is (unfortunately, or perhaps fortunately) now known, is a play so significant that it merits its own Wikipedia article. The short version is that Merkle didn’t advance to second on what would have been a game-winning hit, and what looked to be a 2-1 Giants victory in the late days of a tight pennant race was instead ruled a 1-1 tie. The Cubs and Giants ended the season tied for first place, and were forced to play a makeup game. The Cubs beat the Giants, taking the NL pennant and going on to win the World Series.

Merkle didn’t exactly go on to be a superstar, but he posted mostly respectable numbers for the Giants. He also gained a reputation amongst his colleagues as a smart baseball mind, in spite of his infamous baserunning error.

In August of 1915, Merkle was traded from the Giants to the Robins for catcher Lew McCarty. The New York Times article about the trade explained that, “The deal will give the Giants much needed strength behind the bat, while Merkle is badly needed in view of Jake Daubert‘s disability.”

Indeed, McCarty was in the midst of an excellent season for Brooklyn when he was traded (batting .313 on the year), while Merkle was batting a comparably paltry .237. But the temporary loss of Daubert (the 1913 MVP, the first in Dodger history to win the award) forced the Robins’ hand.

Daubert’s “disability” evidently wasn’t that big of an issue, though, as he was back in Brooklyn’s starting lineup in early September, appearing to have missed about two weeks of play. Merkle spelled Daubert occasionally, but mostly served as a pinch hitter and, on a couple of occasions, an outfielder.

That Brooklyn team went on to win the National League pennant, before losing the World Series in five games to the Red Sox. The Giants finished the season in fourth place.

Merkle appeared in just two games for the Robins in 1917. Since the Robins had Daubert, they had little use for Merkle’s services. Merkle was sold to, of all teams, the Cubs, where he served as their regular first baseman for the next four seasons.

I included Merkle for two main reasons. For one, Merkle’s name is highly recognizable to baseball fans. However, this is perhaps most interesting because it’s a direct trade between the Dodgers and Giants, the second ever.

——-

Come back tomorrow for part two, which spans from the late-1920s through the mid-1980s.

======

Special thanks to Baseball-Reference, the Society for American Baseball Research, Baseball Almanac, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame for making this possible. Additional research conducted via ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog