Clayton Kershaw made his 2019 debut against the Reds last night, and it went extremely well. Kershaw pitched seven strong innings, striking out six, walking none, and allowing just two runs. He faced one batter over the minimum after allowing a first inning Yasiel Puig home run.

After such an unusual spring with time missed due to shoulder problems, it’s hard to view last night’s start as anything other than an extremely positive result. There were a few things in particular worth noting in that outing.

Obviously one start is an absurdly small sample size, so these are more factors to watch going forward than any indicators of change. If the following notes are still true after a few more starts, then we can dive into more substantive analysis. Still, they were interesting and worth noting.

He wasn’t throwing very hard

In his first start of the year, Kershaw averaged 90.1 mph on his fastball. That’s down 1.2 mph from last season’s average and 0.8 mph from last year’s playoffs. It was his lowest average fastball velocity of any start of his career, other than the May 2018 outing in which he hurt his back mid-start.

That’s discouraging, especially since Kershaw has generally not been a slow starter in his career — his April velocities have usually represented where he’s going to be for the rest of the season. However, Kershaw has never had a spring like this one. It’s possible that he could rebound to last year’s levels with a few more starts to more adequately prepare him for the season. Concern is definitely warranted, but it’s too early to panic.

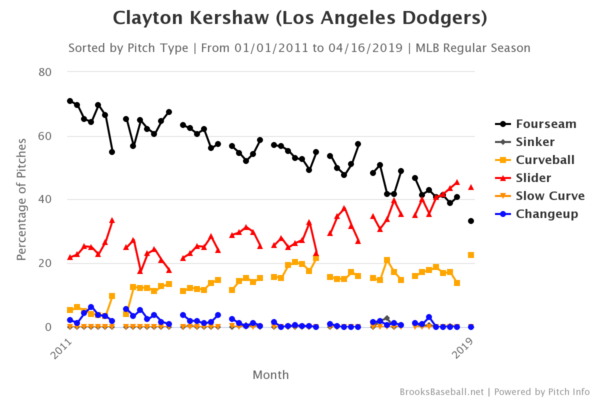

He wasn’t throwing many fastballs

Kershaw threw 28 fastballs among his 84 pitches in yesterday’s outing, a rate of just 33%. The rest of his pitches were all sliders and curves (if you were wondering if Kershaw was going to adjust to his velocity situation by throwing more changeups, thus far the answer appears to be “no”). This is a continuation of a long-term trend:

Still, last night’s start (the only data point from 2019) sticks out. It was the second-lowest fastball use rate of any start in Kershaw’s career, trailing only one start against the Giants last August. According to Baseball Savant, Kershaw’s start featured the seventh-lowest fastball rate among any from 2019 thus far. Two of the other starts in that category belong to teammates Ross Stripling and Kenta Maeda.

He threw a lot of curveballs

Somewhat surprisingly, Kershaw did not replace his missing fastballs with more sliders, which the trend on the above chart shows. Instead, he mixed in curves at a rate we haven’t really seen since he started featuring his slider more frequently to fuel his 2011 breakout.

Kershaw has made 264 regular season appearances in front of pitch tracking cameras since the start of the 2010 season. Last night’s curveball rate (22.6%) was the 8th-highest among any of them. He only exceeded that rate once last year. Kershaw’s curve use has been a source of frustration as his slider began to fade in quality, because that curve still looks like this:

It is rude to GIF a pitcher hitting, but I couldn't help myself pic.twitter.com/U6Ys1kiuG0

— Daniel Brim (@DanielBrim) April 16, 2019

Why throw more flat sliders while keeping the curve use rate the same when the curve still looks like one of the best in baseball? Maybe there’s finally an adjustment happening here. We definitely need more data to see if last night’s usage rate spike was just a response to how the curve felt in the bullpen or to a particular scouting report.

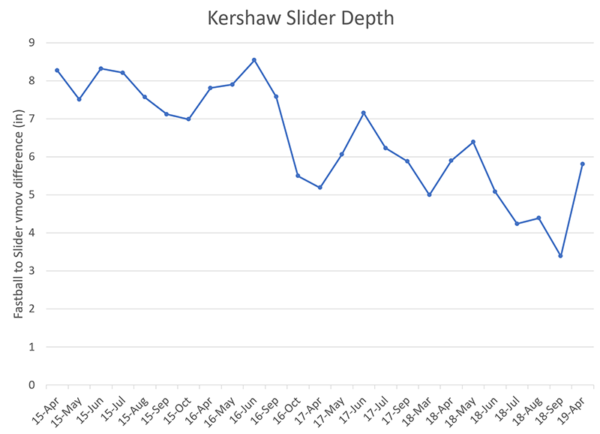

His slider had more depth

This one is perhaps the most interesting. In this case we’ll define the “depth” of a slider as the difference in vertical movement from the fastball. This is particularly important for Kershaw due to his over-the-top arm slot, since that vertical movement difference is what causes right-handed batters to swing over the pitch. Kershaw’s slider depth has been eroding gradually for a few years, but last night’s start saw it tick up to a more reasonable level:

Last night’s slider depth is back to where Kershaw was before his DL stints last season, and was close to his 2017 average. It’s still less than where he was during his peak, but it was a big step in the right direction. This is also heavily subject to sample size caveats, so it’s something that needs to be watched for a few more starts.

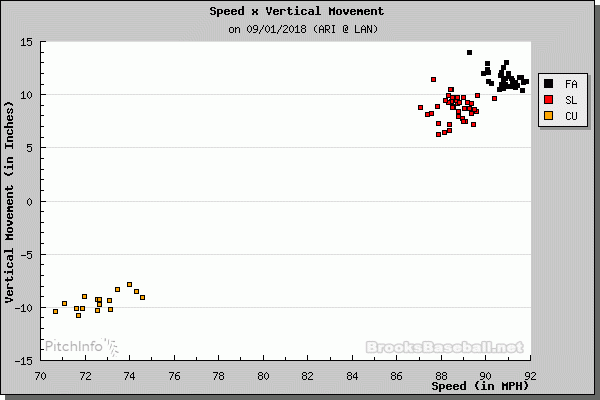

The practical effect of this is that the slider looks less like the fastball. Here is a movement plot of Kershaw’s pitches from a start late last season:

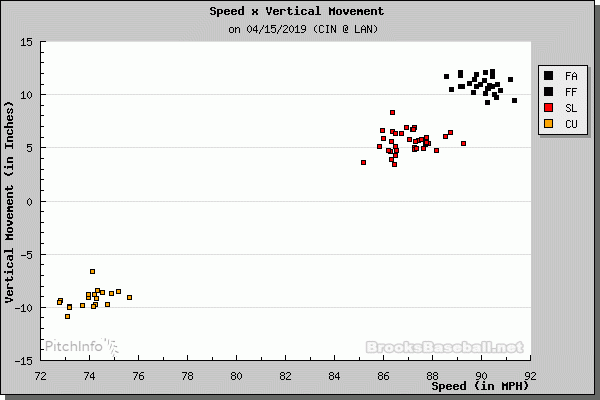

See how the red points (sliders) and black points (fastballs) bleed together? That’s a bad thing. Instead of having three pitches, Kershaw had two and a half. This led to fewer missed bats and more predictability. By contrast, here’s what the same plot looked like in last night’s start:

Now there’s more breathing room between the two, allowing the slider to break further away from the bat. It led to more pitches that looked like this:

Seems promising.

He missed a lot of bats

Kershaw induced a 16.7% missed swing per pitch rate in his start last night, largely due to the factors outlined above. That would have been the third-highest rate among all of his starts in 2018. His whiff-per-swing rate also matched some of his best from last season. His six strikeouts in seven innings undersells how many bats he missed, as many of those missed swings came earlier in counts.

——

With Kershaw, consistency is going to be key, and we won’t know about that consistency until he gets more starts under his belt. Obviously, the most concerning thing right now is that his fastball velocity is lower than ever. He’s responding to that by throwing fewer of them, and the sustainability of that approach is also questionable.

Kershaw’s biggest issue in 2017 and last season was contact control, something that wasn’t touched upon in the points above. We won’t know much about this for a few more starts. It’s also worth remembering that Kershaw wasn’t a ridiculous strikeout machine in the first part of his prime. His K%-BB% and missed swing rates from 2011 to 2013 were about the same as they were in 2018. The difference came from that contact control, especially in home runs allowed. Perhaps the increased slider movement separation (and thus less predictability) can help with that. Perhaps the reduced fastball velocity will make it worse. Perhaps he’ll get hurt by the more lively baseball. Time will tell.

Even so, it’s easy to forget that Kershaw was actually pretty good when he pitched last season. He will probably never be the best pitcher in baseball again, but that’s fine. If last night’s (and last year’s) results were any indication, there’s still a chance for his career to have an extremely good second act.

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog