One story we have been tracking for most of the season at Dodgers Digest is the resurgence of Brandon League. I wrote a story about him being actually useful in late May, which was a complete surprise at the time. Mike followed up in mid-July, and at that point he was still pretty good. Not elite, but better than most other options in a frustrating bullpen. Given what he was last year, the Dodgers would take that every time.

However, League has been struggling lately. I’m not talking about the inning which Justin Turner blew. That was fine. However, since July 29th, League has pitched 5-2/3 innings in eight games. In that span he has walked six batters and struck out two. This rough stretch has raised League’s BB/9 rate from 3.22 to 3.93 and his FIP from 3.18 to 3.45. In other words, his 2014 numbers have gone from comfortably above league average to almost precisely league average in the last three weeks. Still, League’s FIP in 2013 was just a bit under five, so even after including the recent struggles he’s still an improved version of himself, right?

Well, maybe. Something else caught my eye when looking at League’s stats this year and last:

| 2013 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|

| IP | 54.1 | 50.1 |

| FIP | 4.93 | 3.45 |

| xFIP | 4.07 | 4.05 |

League’s FIP has improved from one of the worst in baseball to a bit better than league average, even after the slump. However, his xFIP, which adjusts home runs allowed based on the number of fly balls allowed and the league’s HR/FB ratio, is almost identical. After adjusting for run environment, League’s xFIP is slightly worse than it was last year. League had a real home run problem last season, allowing eight (a 19.0% HR/FB ratio). This season, he has gone in the complete opposite direction, not allowing any in 50 innings pitched.

That’s a bit wordy, so let’s simplify it a bit. Brandon League is striking out more batters this season than he did last season, but he’s also walking more. He’s getting more ground balls, and thus allowing fewer fly balls. All of these changes would completely even out if League gave up home runs on fly balls at the league average rate.

One of my first posts here examined League’s 2013 HR/FB ratio, using batted ball distance to determine if it was artificially inflated. My conclusion was that it was, and a bigger sample with the same distance allowed would result in a rate a bit above the league average. The regression would be to replacement level, but not the complete disaster he was before. It was vaguely positive, or at least more positive than the same calculation was for Chris Perez.

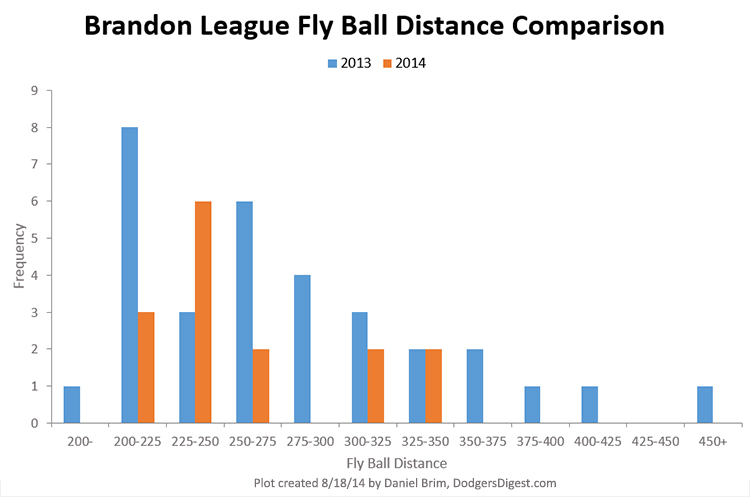

Luckily, the same fly ball data from previous years is available this year, so it’s easy enough to repeat the exercise with a few tweaks. Here’s a histogram comparing League’s 2013 fly ball distances to what he has allowed so far this season:

Not only is the average distance down (276 to 256 feet), but this year’s data is clumped closer together. This season, Brandon League has only allowed four fly balls to travel over 300 feet. He’s only allowed two over 325 feet, the last one hit on May 6th. Last year, League allowed ten fly balls over 300 feet and seven longer than 325 feet.

Statistically, the variance between fly ball distances can be expressed as the “standard deviation.” Even if the fly ball distance remained the same between the two seasons, a higher standard deviation would lead to an expectation of more home runs since. More data spread means more data points at longer distances. Last year, the standard deviation for distance on a Brandon League fly ball was 68.9 feet. This year, it’s 45.9 feet. That dramatic shrink will also lead to better home run prevention.

Since the last time I looked at Brandon League’s fly ball distance, Hardball Times has added “Fly ball distance + 1.5*StDev” (or 93rd percentile fly ball distance) to their hitting correlation tool. Using this tool, it is possible to see if the correlation between fly ball distance and HR/FB ratio is stronger when using the 93rd percentile data instead of the average. Average fly ball distance has a correlation to HR/FB ratio of 0.784, which is pretty strong. When using the 93rd percentile distance, the correlation strengthens to 0.815. Taking the variance into account will improve the quality of HR/FB ratio estimations given past data.

Based on this finding, I’ve estimated League’s 2014 “expected” HR/FB ratio and re-calculated his 2013 ratio. I’ve also used the findings in a modified version of xFIP, replacing the league average HR/FB ratio with the new one found from fly ball distance and standard deviation.

| 2013 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|

| Avg FB Distance | 276.3 | 255.7 |

| StDev | 69.0 | 45.6 |

| Expected HR/FB ratio | 13.4% | 1.7% |

| bxFIP | 3.83 | 3.55 |

Using last year’s fly ball distance data from Baseball Savant, League was expected to allow a HR/FB ratio of 13.3%. That’s better than what he actually allowed, but still above the league average. This year, League’s fly ball distance and standard deviation predicts an expected HR/FB ratio of 1.7%! Not only is League allowing fewer fly balls (just 24 total this season), but the average distance is three feet shorter than and average Dee Gordon fly ball. The spread has shrunk dramatically, too.

Given League’s fly ball distance and variation, he’d only be expected to give up 0.4 home runs this year, while a league average HR/FB ratio (what xFIP assumes) would have an expectation of 2.3. As a result, League’s “batted ball xFIP” (bxFIP) is still significantly better than his xFIP. It was better than his xFIP last year, too.

So, there’s symmetry in League’s numbers which neutralize home runs. Once we look deeper, we can find that League’s new-found home run suppression has a component of skill involved. 24 fly balls isn’t a big sample, so League is one bad pitch away from skewing this year’s expected results. In the meantime, there’s no data point so far this season for which we could say “this ball could have gone out in an alternate reality.”

For now, it’s so far so good for League. He was probably a better pitcher than we recognized in 2013, but he isn’t much worse than we recognize now. If his fly ball distance regresses towards last year, he might be in trouble. In the meantime, as long as he keeps the ball on the ground and stops walking a ton of batters, he’s still useful.

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog