Let’s talk about Joel Peralta. I know, it’s been several days since he was acquired from Tampa Bay, but I’ve been busy, and Dustin stepped up to battle through illness and run down the specifics of the players going and returning. His opinion was that it was a “pretty reasonable trade,” which I tend to agree with, but since then there’s been some (unsurprising) complaints among Dodger fans along the lines of “I can’t believe they traded a young reliever who can top 100 mph for a soon-to-be-39-year-old who just had a 4.41 ERA.”

While there’s a lot I disagree with there — “younger” isn’t instantly “better,” ERA for relievers is silly, and Dominguez’ big arm covers up more than a few flaws — it’s not an entirely ridiculous question. I want to know more. So let’s delve into Peralta a little deeper, and understand why the Dodgers would be interested in this kind of move.

First, some notes from the fans and media who would know him the best, in Tampa Bay.

The Joel Peralta era ends on a bittersweet note. The franchise leader in pitcher appearances had his club option picked up earlier this month but will pitch for a new team (old boss) next season. Even at his advanced age, the right-hander is an above-average reliever despite claims otherwise. He continues to post strikeouts in bunches, miss bats his splitter and controlled the strike zone much better last season. Limited natural ability lends to a thin margin for error. When he is off, he can have stretches of ineffectiveness; however, the overall package – including clubhouse leadership – is a net positive. The fact that the Rays were able to flip his 39-year-old arm for a pair of young pitchers is a testament to his ability. It also means his impact on the club could linger long past his playing days.

Peralta will be 39 in 2015, and last season he struggled to a 4.41 ERA, his highest since 2009, leading some observers to be surprised when the Rays picked up his $2.5 million option. That ERA was belied by excellent strikeout and walk numbers. In 2014, Peralta struck out 27.9% of batters he faced while only walking 5.7%, for a strong 3.11 xFIP. His problem was with the home run. Peralta is and always will be an extreme fly ball pitcher, but last season 11.3% of the fly balls he allowed left the yard — a number far above his career norms. Apparently Andrew Friedman, the new Dodgers and former Rays GM, believes that Peralta has more in the tank than does his former coworker and current Rays GM Matt Silverman. It’s an interesting trade, because the two of them likely had access to the same information regarding Peralta while they were both with the Rays.

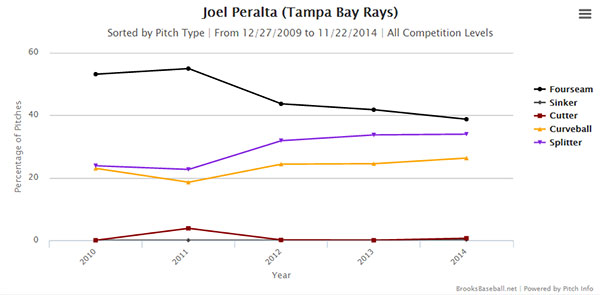

So clearly, don’t be swayed by ERA. Let’s go to the Brooks graphs over the last five years, which cover 2010 in Washington and 2011-14 as a Ray. He’s always been a three-pitch pitcher, but where he used to be heavy on the fastball and mixing in his curve and split now and then, that’s changed since he’s been with Tampa Bay. Now, those three pitches are being used almost equally:

When the split is working, it functions almost like a change, dying away at the last second, like it did to Boston’s Garin Cecchini in September:

That was strike two, and while the next pitch was just a standard fastball, look at how he delivered it, quick-pitching it to throw off Cecchini’s timing:

This kind of trickery is something of a theme for Peralta, which I suppose makes sense for a guy who didn’t make the big leagues until he was 29. Least year, Grantland’s Jonah Keri had a fascinating Q&A with Peralta; the entire thing is worth a read, but I’ll share some highlights:

I want to ask you about some of the things you do to keep hitters off balance. One of the things you’ll do is quick-pitch hitters, throw before they’re ready. How did you pick that up and how do you think it helps you?

I started doing it back in 2010 when I was with the Nationals. It just came to my mind that not many guys were doing it, so if I could get at it, hitters might not expect it. I just started practicing it myself. The first time I did it, Pudge Rodriguez was the catcher. He told me it was a good move to do it. And it just went from there. I started doing it more often, started getting guys off balance. It’s really helped me since I started doing it.

Another thing you do is throw a splitter up in the zone. Usually a splitter will dive out of the strike zone and get hitters to swing over top of it. When a pitcher throws one up in the zone, you’ll hear announcers say, “Oh, he hung that pitch.” But you’re doing it on purpose, almost like a changeup. What made you decide to start doing that?

The split-finger — that’s the pitch that got me here and kept me here in the bigs. I’m able to get lefties out with it. When the split is going good, they see the ball up in the zone, even if it’s up, it’s moving, and they’ll swing at it. And that’s what I want: for them to swing at that pitch. It’s not always a pitch you can control for a strike but it can be hard for hitters to make good contact on it, too.

Of note from that piece: Peralta is recognized as being “kind of bridge between the Latin players and the Caucasian players,” which certainly wouldn’t be a bad thing on a team often accused — fairly or not — of having clubhouse issues.

But what about that ERA? From 2010-12, Peralta was essentially the same pitcher as Huston Street, just without the saves because he was a setup man. In 2013-14, he was again essentially the same pitcher as Street, at least in terms of FIP & xFIP, but doing it in 46 more innings, so overall he was adding more value, but with a huge difference in LOB% that allowed more runs to score. And in terms of ERA/FIP/xFIP, Peralta has never been the kind of guy who always outperforms or underperforms; in fact, he’s always been almost exactly dead on, with a career 3.92 ERA, 3.91 FIP, 3.91 xFIP.

In 2014, that dynamic changed. His 4.41 ERA was wildly above his 3.40 FIP, and while that’s partially because his HR rate was up from 2013, it also wasn’t much different from his career mark. So what happened? BABIP, partially, because his .307 mark was easily his highest since he was a Rockie in 2009. That can partially be chalked up to bad batted-ball luck, though with a pitcher of his age, it’s risky to simply say “bad luck” and leave it at that. No, here’s what the real issue was. It’s not that he was getting crushed. It’s that when he was allowing hits, they were coming at the worst possible time:

Peralta, high leverage, career: .232/.309/.441

Peralta, high leverage, 2014: .279/.330/.512

Meanwhile, in 2013, that mark was an excellent .193/.298/.386. I can believe that an old pitcher can lose his durability, or his velocity, or his best pitch. I can’t believe that a pitcher who has generally been good in big spots could suddenly forget how to pitch in those spots, especially when we’re talking about a sample of fewer than 100 plate appearances. Obviously, allowing a hit in a high leverage spot is going to allow more runs to score than the same pitch & hit without men on base. There have been a few examples of pitchers who just couldn’t handle the pressure, but that’s been few and far between, and it doesn’t seem to apply here. Timing and sequencing, as we’ve generally learned, matter in runs and wins, but aren’t really repeatable skills.

If you believe that Peralta can still miss bats — and he had the second-highest K%-BB% of his career last year, a top-30 number among pitchers with at least 50 innings and basically the same as Felix Hernandez & Masahiro Tanaka — then you can buy into the fact that some issues in big spots aren’t the sign of imminent downfall. That’s why we have FIP to counteract ERA in the first place.

It seems clear to me that Peralta is an interesting guy to have around, so the roster spot isn’t a problem. The $2.5m certainly isn’t a problem. Adam Liberatore, who came with Peralta from Tampa Bay, seems to be a useful depth guy, so that’s not a problem either. The only way this becomes a problem is if you think that Dominguez can overcome his sore shoulder, lack of command, and straight fastball to harness that overwhelming heat. If he can, he’s a star. If he can’t, he’s a Quad-A guy. There’s no shortage of ranges in possible outcomes for him. It’s a risk, of course. But there are fewer bets that are lower odds than on inconsistent non-star relievers with drug histories, right?

I get why the regular fan hates this deal. But for the cost of $2.5m and a reliever we’ll probably have forgotten about by this time next year, it’s more than a worthwhile risk. Age is just a number. So are FIP and K%. This was a worthwhile trade.

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog