“Slow start” seems to undersell just how much Jimmy Rollins has underachieved for almost the first two months of 2015, and that’s only exacerbated by the fact that the rest of the Dodgers offense is achieving what not even the biggest homer could’ve imagined.

Rollins will obviously be better than his current .172/.255/.295/.551 line (well, it is already now), if for no other reason than because his BABIP of .194 would be the worst in the post-war era. And yet despite knowing he’ll improve, I’m becoming increasingly more concerned with his performance to date. My concern isn’t that Rollins has suddenly become the worst hitter of all time or that the results aren’t there. My concern is that even when his luck corrects, it still won’t be as much of a bounce back as people are hoping because of a hitting profile that paints a bleak picture.

*Stats As Of May 14 (5/9, 2 2B, HR, BB Since Then, Of Course)

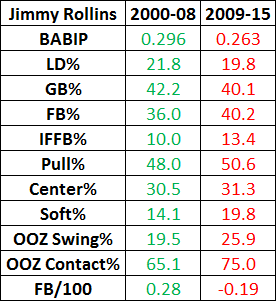

The year endpoints are setup the way they are because that’s when Rollins’ profile began to shift significantly. Prior to 2009, Rollins had a relatively normal BABIP around league average, but since it’s fallen off a cliff to .263. That’s happened over thousands of plate appearances and something we should now consider his new norm, so rather than expecting regression to the mean of .300 or so, it should actually be around .260. To an extent, that was already factored into projections, and he still figured to be a fringe-average hitter in 2015, but my concern is whether the slide has gone to the next level.

Rollins’ line drives have come down and the fly balls have gone up, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. However, when a great number of said fly balls are nothing but can-of-corn infield flies and lazy fly balls due to weak contact, the bad luck becomes more and more deserved. In 2015, he’s actually technically hitting the ball “hard” as frequently as he has in the last five years, but in aggregate, his average velocity off the bat is fifth-worst in the MLB. That trend of weak contact seems unfortunately sustainable, as it can be explained by the fact that Rollins is not only expanding the zone more, but is also making more contact when he does expand the zone.

Most alarming are his struggles against fastballs. FB/100 represents runs above average against fastballs per 100 pitches, which used to be a strength of his, and he was known as a fastball hitter. Now though, Rollins has declined well into negative territory, suggesting that his bat speed is a serious problem and he hasn’t been able to find a way to effectively compensate.

From a scouting perspective, Rollins seems to have shortened his swing this year in an attempt to get around on more plus velocity fastballs, but given the profile so far, one has to wonder if the negatives may be outweighing the positives. The attempt at compensation has him pulling the ball more, but as a result he’s become easier and easier to shift, going to the opposite side now only 18.1% of the time in recent years, which is actually down to 14.0% in 2015. As such, his 2015 spray chart on grounders looks like this (switch hitter but primarily from the left side)…

…and more often Rollins will get results like two games ago where even when he does hit a hard grounder up the middle, they’re shifted for an easy out. Heck, even his now weaker contact on the ground should theoretically lead to more frequent infield hits (think Ichiro Suzuki or Dee Gordon), but that only applies if they’re placed to the opposite field and not pulled to second base like Rollins has frequently done.

Furthermore, while his walk rate was a career-high last year and has been continuing to go in that direction this year, his strikeouts have increased four consecutive years and is up to career-high 19.7% this year. Harder to rely on balls-in-play luck when the balls aren’t going into play.

So while there isn’t one single factor that you can point to as a reason that his performance in the batter’s box might not bounce back as far as before, if we combine weaker overall contact, more fly balls and more strikeouts, and him becoming an increasingly shiftable hitter, it’s all a bit scary to think about what might happen if the Dodgers need 400 more plate appearances out of him.

—–

At the time of the Rollins trade, I was (and still am) a supporter, and that deal had the least pushback out of all the off-season moves; the Dodgers had a gaping hole at short and filled it with a dependably above-average player. So while I’d still love to be wrong about the degree of Rollins’ coming recovery in 2015 — and maybe he’ll make another mechanical adjustment, who knows? — the signs simply aren’t promising that the Dodgers will even get the average offensive production they were likely hoping for.

Perhaps the scariest part is that the Dodgers don’t have a much better option. Rollins was supposed to be a bridge to prospect Corey Seager, but that bridge now seems rickety and has limited options for repair — a full season of Justin Turner or Enrique Hernandez at short would be potentially horrifying, at least defensively. So unless Seager catches fire in AAA and convinces the Dodgers he can handle short, the team and fans will simply have to hope everything turns around for Rollins in a major way, but based on his indicators so far this year, it seems hope might be all there is to it.

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog