Welcome to part 2 of our series on Giants who became Dodgers, inspired by the Sergio Romo signing. This segment spans several decades, starting in the 1920s and ending in the 1980s. A few of the entries are indicative of just how heated the Dodgers/Giants rivalry was at the heart of the 20th century. This post also features two of the three trades made between the two organizations since they relocated to the west coast.

—–

Giants who became Dodgers, part 1: 1890s to 1910s

—–

Years with Giants: 1925-1937

Years with Dodgers: 1937-1943

Freddie Fitzsimmons began his 19-year career with the New York Giants at the age of 23. Fitzsimmons, a knuckleballer, experienced the ups and downs that come with the uncertainty of that signature pitch; in about half of his major league seasons, he recorded more walks than strikeouts. But for the better part of 13 seasons, Fitzsimmons was a solid part of the Giants’ rotation, while also occasionally stepping in as a reliever.

In June of 1937, the Giants and Dodgers completed a trade for just the fourth time, swapping pitchers. Brooklyn parted ways with 22-year-old right hander Tom Baker, and in exchange received the veteran Fitzsimmons. Described by John Drebinger of the New York Times as a “chubby knuckleball expert,” “Fat Freddie” filled an immediate need for starting pitching on the Dodgers’ end.

Though Brooklyn manager Burleigh Grimes “really hated to part with the young Baker,” whom he “considered one of the finest prospects to come up in years,” it turned out he didn’t have much to regret. Baker only made two major league appearances after the 1937 season, a pair of relief outings in September of 1938. He played two more years in the minors before retiring from professional ball at the age of 27.

If nothing else, the acquisition of Fitzsimmons could have been interpreted as a preventative move — Fitzsimmons had, historically, been at his best against the Dodgers. But this seems pretty clearly to be a trade that the Dodgers won. Fitzsimmons didn’t finish 1937 very strongly, but he went on to pitch for parts of six seasons for Brooklyn, posting a couple more solid years (particularly, 1938 and 1940) before his time was through. He didn’t log as many innings as he did in his younger days, but the Dodgers won more of his starts than they lost.

Fitzsimmons was part of one pennant-winning Dodgers team, in 1941. He pitched seven scoreless innings in Game 3 against the Yankees before a line drive off the knee forced him to come out. The Dodgers eventually lost, 2-1.

Fitzsimmons’s involvement in baseball continued after his retirement, and included a short-and-largely-unsuccessful managerial stint with the Phillies, as well as a few coaching gigs.

—–

Years with Giants: 1945; 1950-1955

Years with Dodgers: 1956-1957

In the early days of his career, Sal Maglie was the bane of the Dodgers’ existence. Not only did he frequently triumph over them, he was as menacing an opponent as they came. “On the mound,” Joseph Durso wrote in Maglie’s New York Times obituary, “Maglie had a gaunt look, a grim expression, a stubble beard, a great curveball — and a high, hard one that earned him the nickname Sal the Barber.”

Maglie played 10 major league seasons, which is impressive considering that his major league debut came at the age of 28, and even more impressive considering the four-year hiatus between his rookie season and his next big league start. Maglie’s choice to jump to the Mexican League in 1946 meant that, under the rules of the day, he’d be banned from playing in MLB for another five years. When commissioner Happy Chandler lifted the ban in 1950, Maglie returned to the Giants.

At age 33, Maglie pitched his first full major league season, and he was excellent. He made 16 starts, nine of which were complete games and five of which were shutouts (that year’s MLB best). In addition, he made 31 relief appearances. His combined efforts were good for an MLB-leading 2.71 ERA.

Maglie also used his comeback season to establish his reputation as a mean son of a gun. In a game against the Dodgers on June 19th, Maglie threw a fastball behind Gil Hodges‘s head that came far too close to hitting him. Later that game, Maglie nearly hit Hodges again, and then did hit Carl Furillo. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle noted that, though Maglie was not officially admonished, the Dodgers were well convinced of his intentions: “The umpire refused to read the pitcher’s mind but the Dodger bench maintained that Maglie’s mind was an open book.”

Maglie became basically a full-time starter the following season, in which he won an MLB-best 23 games. He was the starting pitcher in the final game of the 1951 season, the famous “Shot Heard ‘Round The World” game. He pitched eight innings, and was set to take the loss before Bobby Thomson stepped in and did his thing.

Maglie was similarly dominant in 1952. He faced the Dodgers eight times that year, and the Giants took six of those meetings.

1953, Maglie’s age-36 season, was a down year for him due to a back injury, but he rebounded nicely in 1954. Halfway through the 1955 season, the Giants sold Maglie to Cleveland, where he only appeared in 10 games for the remainder of the year.

In 1956, Maglie made it into two games for Cleveland. The Dodgers took advantage of Maglie’s underrating in a big way, per his SABR bio:

In what may be the greatest bargain in baseball history, the Dodgers’ astute general manager Buzzie Bavasi out-bargained the Indians’ Hank Greenberg and obtained Maglie for a mere $100.

Newspapers of the day repeatedly stressed Maglie’s regular success over Brooklyn. When asked by reporters about his supposed hate for the Dodgers, and his rivalry with Furillo, Maglie responded as such:

“‘Hate’ is just a saying, I guess,” Sal smiled. “I don’t hate anybody. But I’ve always borne down a little harder against the top teams — and Brooklyn is a top team.

“People said all I had to do was throw my glove on the field to beat the Dodgers, but that’s not true. I really think I had it when I beat ’em so much.”

Asked about his alleged feud with Carl Furillo, Maglie said: “I don’t really know Furillo. We never had any words. I think Carl’s anger was directed more at Leo Durocher, anyway. I can say I don’t throw at any player to hit him. It’s easy to hit a man if you want.”

Just how did the Brooklyn faithful take Maglie joining their team, though? Once again, per his SABR bio:

Dodger fans, at first horrified to see their team’s nemesis in Dodger blue, soon warmed to Sal as the aging hurler won key games that enabled the Dodgers to gain their final Brooklyn pennant.

Indeed, Maglie won 13 games for the Dodgers in 1956, slipping nicely into a staff with Don Newcombe as its ace and a young Sandy Koufax as its fifth starter. Maglie also started two games in that year’s World Series against the Yankees. Game 1 went well, as he defeated Whitey Ford. Maglie’s eight-inning, two-run effort in Game 5 was respectable; unfortunately, Don Larsen just so happened to pitch a perfect game that day.

Maglie did not play one entire full season with the Dodgers. After 17 starts for Brooklyn in 1957, he was traded to the Yankees, making him the last player to ever play for the New York Giants, the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Yankees while all three were still in New York.

—–

Years with Giants: 1961-1967

Years with Dodgers: 1968-1971

Tom Haller played the first seven of his 12 Major League seasons with the Giants. He was primarily a catcher, though he occasionally filled in as an outfielder and first baseman. A three-time All Star, Haller was known as a great defensive catcher with a strong arm, but he was also an above-average hitter for most of his career — not necessarily by batting average, but certainly in power; while an active player, Haller was fourth amongst catchers in home runs.

In 1965, Haller was involved in an incident that was part of the buildup to the infamous Marichal-Roseboro brawl (as discussed in the following entry). From SABR:

On Thursday, August 19, the Dodgers came into San Francisco for a four-game series. At the time, the Braves led the Dodgers by ½ game and the Giants were in third, one game behind. Everyone was looking for an edge. In the second game of the series, Maury Wills set up to bunt and Haller moved up. Wills pulled back, hitting Haller on the glove. Wills got first base. Later in the game there were harsh words between the Giants bench, especially Marichal, and Dodger catcher John Roseboro.

The aforementioned brawl occurred two days later.

Following the 1967 season, Haller was traded to the Dodgers for infielders Ron Hunt and Nate Oliver. It was the first trade between the two teams in about ten years, and the first since they’d moved to California, and it came as a bit of a shock to Haller (once again, from SABR):

When owner Horace Stoneham told Haller that the Giants were looking to trade him, Tom asked to be traded to a West Coast team. However, he was surprised when he was traded to the hated Dodgers. The Giants need at second base was such that they felt the need to trade Haller. Hunt was installed at second base, allowing Hal Lanier, with a rifle arm, a great glove and range, to stay at shortstop.

It wasn’t just Haller who was surprised, either. Charles Maher of the Los Angeles Times wrote an article entitled “Why Buzzie Dealt With Giants,” which provides some interesting insight into the Dodgers/Giants rivalry from before and after the move:

“When we were back in New York,” [general manager Buzzie Bavasi] said, “the feeling between the fans of the two clubs was even stronger than it is out here. If we had traded one of our stars to the Giants, there could have been an incident as important as the garbage strike.

“Some people may have thought the feeling between Dodger and Giant fans was an act. But it was no act. It was a fact.

“Even when we got out here, we didn’t think it was a good idea to deal too frequently with the Giants. If we did, a lot of their players would no longer be enemies when they came down here. People would be seeing their old friends on the other club. You see too many familiar faces on the other club and you lose the rivalry.

“I firmly believe we were right in not dealing with our closest competitor. I really believe that.”

When asked by Maher why they made the exception for the Haller trade, Bavasi explained that the Dodgers wanted an experienced catcher to work with the young Jeff Torborg, and Haller was who was available. (Bavasi also said that it would “not necessarily” be a while before the Dodgers and Giants made a deal again, and that he’d “be perfectly willing to sit down with them again in 15 years.”)

In spite of the the fact that “the first look at Tom Haller in a Dodger uniform made people think there was a spy in training camp” (per Dan Hafner of the Times), Haller’s transition to Los Angeles went pretty smoothly (one more time, from SABR):

His time in Los Angeles was well spent and he was well-respected by everyone with the team. Fresco Thompson noted that “Pitchers shake off Haller less than any catcher in the league” and Walt Alston stated “Perhaps what I like about him most of all is his spirit and attitude.”

Haller played four full seasons with the Dodgers, and put up a cumulative .276/.344/.393 slash line. He was starting to wear down a bit, though, and, by 1971, was no longer playing 100+ games a season. He was traded to Detroit the following year, where he played his final big league season before retiring at the age of 35.

—–

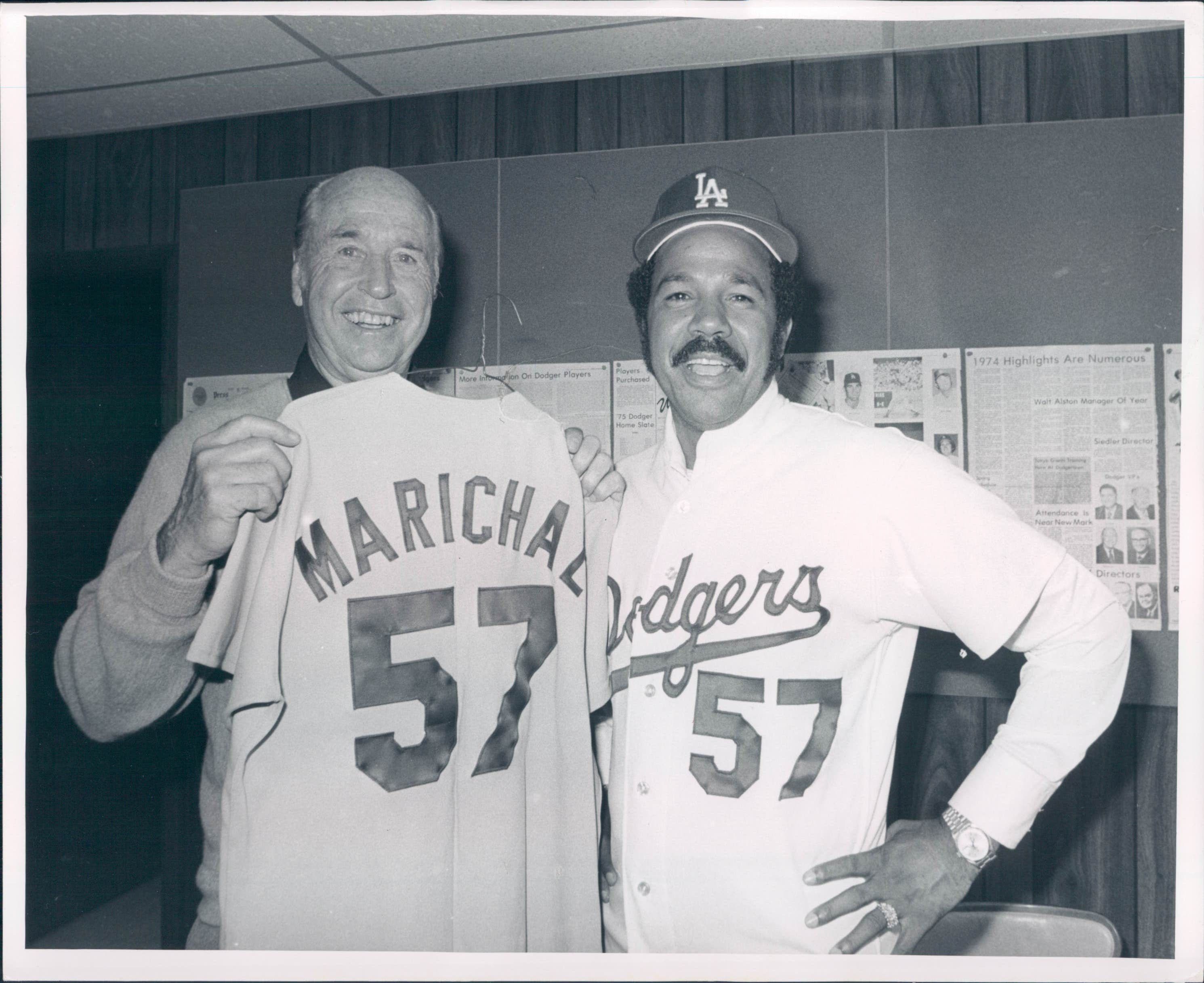

Years with Giants: 1960-1973

Years with Dodgers: 1975

Juan Marichal pitched for the Dodgers in 1975, his final season in the majors. However, his most infamous moment involving the Dodgers took place when he was still with the Giants. That would, of course, be the brawl in which he hit catcher John Roseboro over the head with a bat. For an in-depth look at what happened there, ESPN’s piece from the 50th anniversary does a good job capturing the details and the context of the fight, including the fact that some of Marichal and Roseboro’s anger had nothing to do with baseball:

Real-world events had been a distraction for both players. Marichal was concerned about the civil war that raged in his native Dominican Republic for much of the 1965 major league season. Roseboro, meanwhile, was an African-American man who had just witnessed the Watts riots not far from his home in South Central Los Angeles. A week earlier, smoke from fires set during the riots was visible from Dodger Stadium during games.

Marichal’s animus with the Dodgers was not limited to the Roseboro brawl, though. He also had incidents involving Willie Davis and Bill Buckner.

While Dodger fans may have had plenty of reasons to loathe Marichal, it is undeniable that he was really, really good. The Hall of Famer was a ten-time All Star, and one of the most dominant forces of the pitchers’ paradise that was the 1960s. According to his SABR bio, he was sneaky in his prowess: “Marichal didn’t look overpowering. He looked like a finesse pitcher and usually worked that way, but he could blow away any hitter if he had to.” He was regarded for his pinpoint control, routinely posting some of the best walk numbers.

Marichal was involved in numerous games that were memorable for the right reasons, too. He pitched a no hitter in 1963 and, later that year, he was the victor in arguably the greatest game ever pitched.

Marichal’s last great season came in 1971. That season was followed by two subpar years, after which the Giants sold him to the Red Sox. After a year in Boston, Marichal was released. That offseason, he signed with the Dodgers.

Dodgers players and executives varied in their responses when asked about the signing, but many spoke quite candidly, as reported by Los Angeles Times staff writer Jeff Prugh:

Said left fielder Bill Buckner, who nearly exchanged blows with Marichal after a knockdown pitch incident a few years ago: “I hope he does the job. I’ve talked with him a lot since that happened. What happens on the field in the past doesn’t have anything to do with how things are now.”

Said vice president Al Campanis, who announced the deal: “Listen, nobody hated Juan Marichal more than I did … But there are times when things change, when your affections replace any ill feeling … I’m excited.”

Catcher-outfielder Joe Ferguson: “I don’t think he can pitch anymore. It looks like a publicity thing to me.”

First-baseman Steve Garvey: “If he can help us, fine. We can always used pitching help.”

Injured left-hander Tommy John: “That gives us five good pitchers when I come back.”

Dodger fans didn’t get many opportunities to see Marichal pitch in Blue, as he ended up making just two regular season starts, and only one of which was at Dodger Stadium. He did start an exhibition game against the Angels prior to the beginning of the season, and, per Prugh, got a mainly positive reception from fans.

He drew mostly cheers from a crowd of 18,040 when he jogged from the left-field bullpen to open a game delayed a half-hour by rain. There was only scattered booing when he was introduced at bat in the second inning. And he was cheered appreciatively when he walked to the dugout after retiring 10 of the last 11 batters he faced.

Imagine telling Dodger fans in 1965 that one day, ten years later, Marichal would be cheered at Chavez Ravine.

Marichal’s Dodger career totaled just six innings. He gave up nine runs on nine hits and five walks, and struck out just one batter. After that start, Marichal officially retired from baseball, an unceremonious end to a mostly brilliant, Hall of Fame career.

—–

Years with Giants: 1985

Years with Dodgers: 1986-1987

Catcher Álex Treviño was never all that much of a hitter; rather, according to his SABR bio, “his agility, strong arm, and knowledge kept him employed behind the plate for more than two decades.”

Treviño debuted with the Mets in 1978, and played for both Cincinnati and Atlanta before being traded to San Francisco ahead of the 1985 season. His time with the Giants was brief — just one season — and his playing time was limited — just 179 plate appearances.

When Treviño was traded from the Giants to the Dodgers for outfielder Candy Maldonado that offseason, it was the first trade between the two organizations in nearly two decades. (It turns out that Bavasi’s prediction of 15 years was actually pretty close to accurate.) But the Dodgers, having just traded Steve Yeager, were in need of a catcher to share some of Mike Scioscia‘s duties, and the veteran Treviño seemed like a good fit.

The well-traveled Treviño was happy to come to L.A., as reported by Gordon Edes of the Times:

“I’m Mexican, born and raised,” he said, which makes the deal especially sweet. “This town has a lot of Mexican people, and to get to play with a Mexican superstar like Fernando Valenzuela is going to be quite an experience.”

In fact, when Treviño caught Valenzuela for the first time, they became the first ever all-Mexican battery in MLB history (per SABR).

1986 was one of Treviño’s best seasons at the plate, as he posted his career-highest OPS of .737. However, the following season, his OPS dropped to .618. He was then traded to the Astros. Before retiring, he had brief stints with the Mets and the Reds, played in the minors for the Cardinals and Angels, and, finally, played a few summers in his home town of Monterrey. Today, he works as a Spanish-language radio broadcasters for the Astros.

——

Honorable mentions go to High Pockets Kelly and Freddie Lindstrom, two Hall of Famers who played the bulk of their careers with the Giants, then played their final seasons with the Dodgers. They get mentioned for being Hall of Famers, but their Giants-to-Dodgers stories were not especially interesting.

Come back tomorrow for part 3: the Ned Colletti years!

=====

Special thanks to Baseball-Reference, the Society for American Baseball Research, Baseball Almanac, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame for making this possible. Additional research conducted via ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog

Dodgers Digest Los Angeles Dodgers Baseball Blog